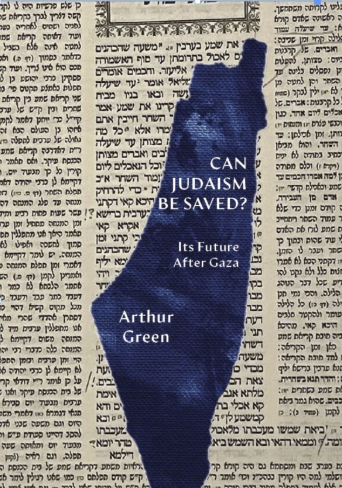

A Book Review: Can Judaism Be Saved? Its Future After Gaza

A Review:

Arthur Green

Can Judaism Be Saved? Its Future After Gaza

Ben Yehuda Press, 2025

More than two years after a day that changed everything and nothing, Israelis, Palestinians, Jews, Arabs, and Muslims are all coming around to the point of view of the Civil Rights pioneer Fannie Lou Hamer, who in 1964 told Harlem: “I’m sick and tired of being sick and tired.” But in order to figure out where this will all end, and if it will ever end, we might ask ourselves where it all began. That doesn’t mean October 7, 2023. For that task, we have no better guide than Arthur Green, a legendary figure in American Judaism who for decades has straddled tradition and progress, scholarship and creativity, belief and practice, and authority and invention.

Green’s career has been so distinguished that his 1968 article exploring the links between Judaism and LSD has been all but forgotten–though to be fair, it was written under a pseudonym. Then again, the breadth of vision and the willingness to experiment on display in that article have always marked Green’s work. His latest work, Can Judaism Be Saved? Its Future After Gaza?, doesn’t reach the heights of his 2010 volume Radical Judaism, which ought to be required reading for every Jew–perhaps for every reader. But it does offer us a way to understand what the hell is going on in the Middle East, and a way to move forward. Yes, he advises among other things that Jews welcome “a careful embrace of psychedelic elements.” Far more mind-blowing is Green’s ability to reach deep into Jewish tradition and create an astonishingly learned and broad-minded genealogy of Jewish ideas about otherness– not just the other that is the Jew, but the other’s other, who is the Palestinian–that are used to understand and justify violence and destruction. He also suggests how they might be used to create peace and justice.

It’s not often that we see someone with such a towering command of Jewish traditions and languages, and with such an abiding love for and belief in Israel, speaking hard truths about the current situation. Green never papers over the horrendous events of October 7, the Shoah, or thousands of years of Jewish suffering. That’s what allows him to deplore so convincingly not just the destruction of Gaza in the last two years and recent events on the West Bank, where Netanyau’s government has given half a million settlers free reign in their campaign against Palestinians, but the latest developments in Israel proper, where Arabic was recently demoted to secondary status and the rule of law is in danger in the form of a judiciary that might not be independent any more. But Green sees the scariest conflict between Jew and Jew, which as it turns out is also part of the tradition.

No matter how disturbing the process might be, Green sees the response of Netanyahu’s government as not only inhumane and illegal but profoundly non-Jewish, though that’s complicated, of course. Green is an unapologetic liberal Zionist, which makes him either a dinosaur or a unicorn–that is, extinct or illusionary. He was born to a traditionally religious mother and a father who was a “militant atheist” in Newark, NJ during the war years–which might lead us to ask what was in the water in Newark at mid-century, giving us not only Green but Allen Ginsberg, Philip Roth, Leslie Fiedler, LeRoi Jones/Amiri Baraka, Wayne Shorter, Paul Auster, Richard Meier, Paul Simon, Brian DePalma, Ed Koch, and Lee Lozano, among many, many others?

As a teenager Green studied in the liberal tradition with some of the most important and influential figures of the day, including Joachim Prinz, Max Gruenwald, and David Weiss-Halivni. At Brandeis he studied with Nahum Glazer and Alexander Altman and gravitated toward orthodoxy just as his friend and mentor Zalman Schacher-Shalomi was moving away from Chabad. Green became a disciple of Abraham Joshua Heschel and helped found Havurat Shalom, which pioneered a non-denominational, lay-led approach to Jewish community and worship. He returned to Brandeis for his Ph.D., with a dissertation on Nachman of Bratslav and then taught at the University of Pennsylvania before serving as dean and president of Philadelphia’s Reconstructionist College. He returned to Brandeis in 1993 and a decade later founded the non-denominational rabbinical program at Boston’s Hebrew College. It all adds up to a career that made once-marginal elements of Jewish thought and practice, like interfaith outreach and egalitarian services, central to Jewish life in America, though he considers himself above all a scholar of the history of Hasidism and Jewish mysticism, with twelve books to his name, hundreds of articles, and thousands of speeches and lectures.

Predictably and correctly, Green locates the roots of the current conflict in the ancient tension between ethno-ethnonationalist and universalist tendencies that we see in the Biblical stories of the Patriarchs, between ahavat yisrael (the love of Jews) and ahavat ha-briot (the love of all people)--to put it another way, between the ethnic and ethical. This is, he reminds us, a double legacy, on the one hand a commitment to occupy and safeguard the Holy Land, and on the other hand the obligation to act as willing servants of universal law that grants rights to every human being and all created things.

Though Abraham and his descendants, according to the story, engaged in distressing levels of conflict in accepting God’s promise that they would occupy Canaan forever, there’s not much sense of his people as a separate nation until their sojourn in Egypt, which is for Green a model for the ways in which victimization, exile, suffering, and discrimination creates collective identity, though it can never excuse it.

It’s painful to admit that something other than anti-semitism (the word only dates back to the nineteenth century) is responsible for Judaism’s embrace of a defensive particularism and a protective form of isolationism and separation. But the Hebrew word for “holy” does after all mean “separation.” Still, Green reminds us that the chosen-ness that anti-semites point to was never a foundational principle of Judaism. If anything, the Jews chose God more than God chose the Jews, which we see in the classic midrash in which God first offers Torah to the descendants of Esav and then to the descendants of Moav, both of whom reject it, before finally offering it to the Israelites.

The conquest of Canaan, the rise and fall and rise of the kingdom of Judah, and the construction of Solomon’s Temple were made possible by a growing sense of Hebrew identity, which was only amplified after the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 A.D. Afterwards, Jews who were scattered across the Mediterranean region and the Middle East could no longer unambiguously claim to be practicing a universal faith.

The Jewish Mysticism that spread across Eastern Europe and Ottoman territories after the expulsion in 1492 from Spain and Portugal, where Jews had been reasonably well-integrated into the majority cultures for centuries, was nonetheless associated in part and at times with the supposed uniqueness and superiority of the Jewish people, especially as Jews found new homes, often linguistically and culturally apart from their new neighbors.

Hasidism recognized what was in a sense a new covenant, one that could be even more exclusionary than the old one. For some, perhaps most followers of the founder of Hasidism, the Baal Shem Tov, only Jews were capable of experiencing and serving the divine. That’s ironic, given that the Baal Shem Tov was almost certainly inspired by the Christian and Sufi mystics that he encountered during his years of solitary wandering in the southeast of Poland in the 1730s and 1740s. Other Hasids believed that all humans were made in the image of God, that they were all capable of mirroring and magnifying the divine love of the Jewish God. No wonder Jews in Europe were so divided by Zionism, a “westernized,” secular project that drew from universalist, enlightenment ideals. Still, many early Zionists saw the Palestinians as a distracting irritant at best and an impediment at worst. Meanwhile, the religious parties who invested in Jewish nationalism drew from ideas about Jewish difference and superiority to see Palestinians not simply as inferior but dangerous, even when not armed.

Green traces the decline of collectivist spirit in Israel and the rise of more individualistic thinking to the country’s economic success, which has turned the country upside down and inside out. While secular Israelis could envision co-existence, religious Jews who for a century withheld their full support for the Jewish state–that was the job of moshiach–moved toward acceptance of nominally secular democracy, which they often defined in very broad geographic terms. Many of the “hilltop youth” carrying out what are plainly illegal and immoral acts of terrorism on the West Bank are inspired by ideas about the superiority of Jewish soul, which is not hard to find in the Chabad tradition. That kind of ahavat yisrael is at least in part a defensive reaction to many centuries of discrimination–understandable, but not justifiable if it means victimizing others. As Reb Dylan reminds us, sometimes your enemy is actually your victim.

Green is no politician. His only power comes from what he thinks and says. Yet it is still disappointing to find that his answers, beyond the renovation of our very souls, are matters of meetings, conferences, parties, and labels (which leader of SNCC said that freedom was an endless meeting?). He promotes not a Jewish and Democratic state, but a Democratic Jewish state, even as he worries that it’s too late for such linguistic niceties. He has more hope for organizations like A Land for All, which works for a two-state solution within a confederation framework, and Smol Emuni, which comes to these matters from a perspective that is left wing but orthodox, if that makes any sense. But in today’s world, sense will only take you so far. Thankfully, in addition to his stunning grasp of the totality of Jewish history and tradition, Green has embraced a resistance to dogma, a fearless resistance to received wisdom. He rejects the certainty emanating from Washington, D.C., Jerusalem, and Ramallah that is the sure sign of a charlatan. Instead, he follows in the spirit of Mark Twain, who argued: “It ain’t what you don’t know that gets you into trouble. It’s what you know for sure that just ain’t so.”

We all need a way of navigating what is surely the most tumultuous period in Jewish history in decades. Green, who has experienced a distressing tumult in his own life of late, begins and ends this book by citing Schachter-Shalomi’s belief that Judaism is a derech in avoyde, a path of service. Serving what, we must ask, and whom, and how? For Green, attacking what political scientists call “the spiral of silence” means taking a good, hard look at Jewish tradition, and being willing to challenge and change it, even if it means being labelled a moser, which Green translates as “traitor.” A better translation is “informer,” but is even the kind of information Green has to offer enough? We will all need not only our heads, but our hearts, and our hands, this time around.

Special thanks to Tamarah Benima and Roy Carton for their wisdom, generosity, and inspiration.