the places you remember

There are places that evoke sensations of home. We all have them, even if we sometimes don't recognize them, and even if we've been away for decades.

I lived in Lynchburg, Virginia, until leaving for college, but because I have returned there frequently to see family and friends, those memorable places have remained very real to me.

The few that made it into this compilation—I've decided to call them McNuggets—speak not to some grandiose theme in my life, nor are they necessarily unique to Lynchburg. They hold special significance to me because of the psychological tattoos they inked on my memory and the contributions they each made to my sense of place and to my sense of self.

But first, let's put the immediate and very common misconception to rest: my hometown in central Virginia did not earn its name by summarily and extrajudicially executing Black people.

Granted, Lynchburg has needed to overcome and move beyond its shameful history of glorifying the Confederacy, actively participating in the slavery trade and cruelly enforcing Jim Crow segregation upon its Black citizens. But John Lynch, a quaker, operated a ferry across the James River, and it is for him that the town was named.

Stadium

Each summer my little sister Tina (who’ll be 68 in April … how did that happen?) and I spend a leisurely evening together at Lynchburg's City Stadium where the Hill Cats play baseball.

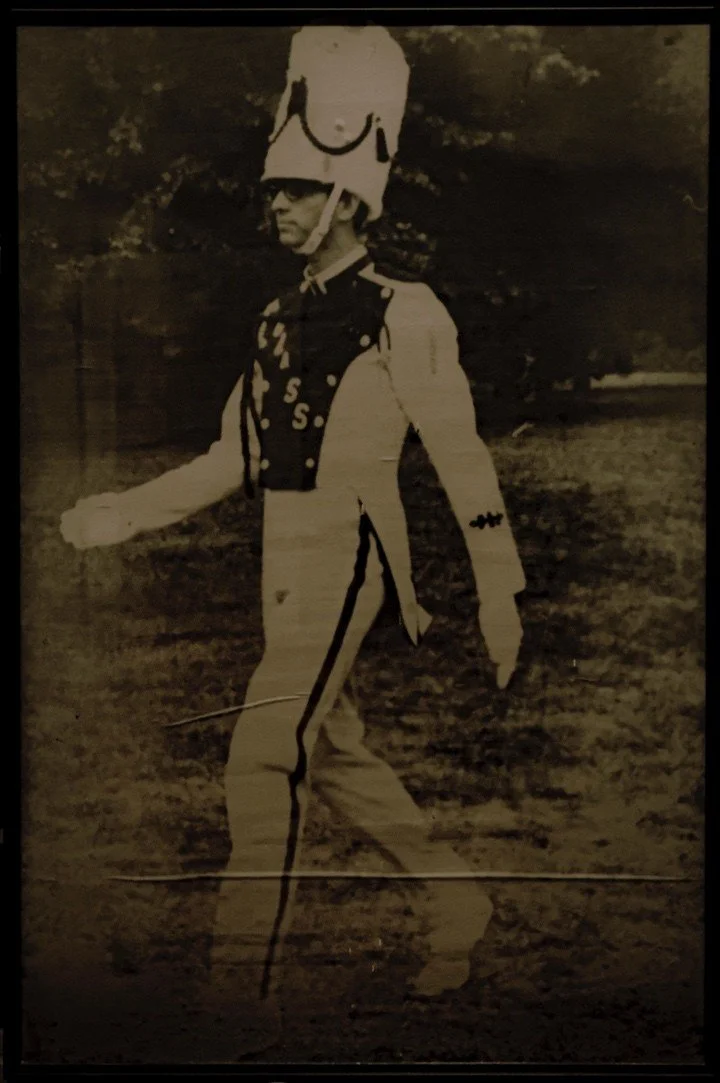

Last year, before the first pitch we wandered around a bit and took pictures. I happened to look beyond the baseball stadium's third-base line into the adjacent stadium, the one where high school football games were played and where I had spent many a high-school Friday night, wearing the uniform of a marching drummer and for two years, as the drum major. The football stadium looked familiar but much smaller than I remembered it.

By the time I was promoted to drum major at the start of my junior year, I had performed in The Stadium with the marching band 10 times. Our halftime shows were only about seven minutes long, but for those seven minutes we filled the 9,000-seat space with pretty good music and the football field with precision marching.

As drum major my job was to lead the band's movement and conduct their musical performance. I got the job because the uniform fit nicely on my long frame, but I made the job mine through the choreography I executed.

I had been to summer camp for drum majors and learned to move in perfect time with the music. I practiced and perfected my high-kicking strut from one end of the field to the other, landing on the spot from which to face the band then to lead and synchronize them with precise and exaggerated hand and body signals. It was thrilling to see and hear them respond to me, and when we finished, we marched from the field with the adulation of the appreciative crowd washing over us.

I can almost still hear the cheering, 50 years later.

ER

At age 16 I took a summer job in the Out-Patient Department, later to be called the "ER" at Lynchburg General Hospital. My duties varied from making beds with hospital corners and sterilizing instruments, to holding a shrieking baby while a pediatrician repaired its lacerated cheek.

I witnessed my first post-mortem examination. On his way to the morgue Dr. Reid, the coroner, grabbed me to assist him in retrieving a bullet from the brain of a murder victim.

I returned to the hospital recently when my mom's terminal illness terminated there. It was not easy to recognize the place because it had metastasized a great deal as the healthcare industry expanded to meet the ever-increasing need.

It's not even called Lynchburg General Hospital anymore. Like many public hospitals, this one has been privatized. It has a corporate-sounding name that sounds like it could be a soft drink, and there’s a freaking helicopter landing pad out back where I used to wait in ambush as adorable student nurses in starchy white caps and white bib aprons, and stealthy, yet sensible white shoes disappeared into the entrance of the student nurses' fortress-like dormitory.

It was the baby's lacerated cheek that almost knocked me out of the job. Dr. Vaden completed the stitches efficiently, but when a wounded infant is screaming in your ear time passes very slowly. Finally, the work was finished. I had cleaned up the trauma room and prepared everything for the next case when I caught up with Dr. Vaden, who was writing up his report for the chart.

"Dr. Vaden, are the kids always so loud? How do you stand it?" He said, "I do it because they get better."

Train Station

Kemper Street Station is all different too, but the sound of baggage wagon wheels on the cobblestone pavement takes me right back to the time of immense Southern Railroad trains on their way to or from New York, with white table-clothed tables in the dining car. In the pre-microwave era the apple pie was served hot from the oven, and the chicken was fried not grilled.

I owe my very existence to that station and its trains that ran north to New York where my mother lived and south to Lynchburg where my father lived. Their courtship, and thus my conception, relied on those trains.

Expressway

Want to experience the scary side of my hometown? Spend a few wholly terrifying minutes driving the Lynchburg Expressway.

It almost looks like four lanes of the actual limited access highways such as the interstates and beltways, so drivers tend to behave as if it were. But, it's not. It twists and turns, the lanes are narrow, and the entrance ramps are either too short or non-existent. Because it's known as The Expressway and its posted speed limit varies from 55 to 65, everyone is speeding.

On many a night I found myself on the Expressway heading home late after dropping my date at her house on the other side of town. On any one of those nights, the Expressway could have easily claimed me as another victim, especially when beer became part of my social life.

Band Room

I must have spent 10,000 hours in the semi-circular Band Room at E.C. Glass High School. We were positioned in a more-or-less conventional concert band arrangement, i.e., woodwinds in front, brass behind them and percussion in the rear.

I became a percussionist a few months after my orthodontist snatched the lovely brass, melodic alto saxophone from my overbite and cemented the metal bands and wires of braces to my teeth. I didn't have much time to mourn the loss of that beautiful horn because I was quickly picking up the rudiments of drumming as a result of daily lessons of a most unusual type and in a most annoying place: the school bus where George Calvert tutored me.

Together we banged away on the stainless steel, tubular grab bars on the top of every seat-back on the 1960s vintage city buses. To qualify for the high school marching band I learned the rudiments of drumming: PAR-a-Diddle, fLAM, fLam-a-DIDDLE, and the snappy Flam-a-CUE. The Rolls from 5-stroke roll to 17-stroke roll: Tippy Tippy Tippy Tippy Tippy Tippy Tippy Tippy TAP. We were oblivious to how much the other bus riders were irritated, and at our recent reunion George and I compared our regrets at having ruined our friends' morning commute.

I recently apologized to our classmates in a Facebook post. I was surprised and delighted to receive the following response from a dear classmate:

“I have SUCH wonderful memories, looking forward to you and George, sitting on the back of the bus seats, banging out rhythms together. It was not an assault, but another world, where folks could play and learn and I found it extremely fun, and very cool. I was impressed, in awe. [There was no music at my house, and that is not a metaphor. It was a somber place, very little light.] So you two were like an open window, letting in air … and possibilities. I was wowed.”

During football and basketball seasons, I was part of what has come to known as a "drumline" but had no such identity a half-century ago. Also happening to me without my knowledge was a growing appreciation for rhythm and harmony among instruments and their players; developing the perceptual capacity to hear myself as well as hearing what's coming from the ensemble of which I am a part. The band is a human amplifier, and I grew to love being inside of it.

Of these few places, none has remained more prominent than the band room and the musical experiences I had there. Music is in my life daily. Each time I pick up my four-string bass guitar I'm reminded of the four copper-kettle timpani set I played when I was 17.

My instrument and place have changed, but the memory persists.