Modernism and the Hippies

One of the subjects I’ve hoped this website might investigate is where the ideas that so galvanized Our Generation, back when we were more galvanizable, originated. I call that mix of ideas “hippy thought,” and I mean by it the multiple challenges to “straight” understandings and values promulgated by anti-Vietnam War, marijuana-smoking, LSD-curious, ripped-blue-jean-wearing, rock-‘n’-roll-dancing young people in the late 1960s and 1970s.

I suspect many of the ideas that filled our heads back then are still contributing to the way we look at the world today. That does at least seem to be the case for the way I look at the world, although you wouldn’t necessarily know it from the way I’ve spent the last five decades.

Previous installments of this investigation—this is the introduction to it— have considered the influence of Whitman and Thoreau, and of the Beatniks. Here I want to look at the influence of something that would not have come to mind back in the day as readily as Whitman, Thoreau and the Beatniks: modernism. Indeed, a lot of hippie thought seemed decidedly unmodern.

For they—okay we, many of us—were intrigued with old dungarees, acoustic instruments, folk tunes, soy beans, ancient Eastern religions, country living and lots of other not-modern stuff. And we, most of us, had little use for shiny new anythings, with the possible exception of crock-pots, Telecasters and the latest album by Country Joe and the Fish.

Nonetheless, the hippie view of the world was very much a product of the 20th century, and the outstanding aesthetic and intellectual movement of the twentieth century was modernism.

Hippies would not have been as groovy, as far out, without having inhaled, if only second hand, healthy doses of modernists like Picasso, Virginia Woolf, Frank Lloyd Wright, James Joyce and John Coltrane.

But to make this point I first need to chop modernism in half. For I believe there were really two modernisms, and only one of them was responsible for helping turn us on.

Both those modernisms, interestingly enough, first arrived at the very end of the 19th century in Vienna. Indeed, each of the two modernisms manifested itself as a building within six months of each other, within two blocks of each other.

One modernism—and therefore one 20th-century aesthetic and intellectual movement—emphasized straight lines, clear logic and the subtraction of the decorative, the artificial. Its promulgators, beginning with the architect Adolf Loos, who designed one of those Vienna buildings, ruthlessly stripped away artifice and decoration.

The Loos-designed Café Museum opened in 1899 in Vienna and was entirely, shockingly different than the grand, ornate intensively-decorated buildings that lined the nearby Ringstrasse—those buildings that so impress tourists today. Loos had no use for such frills and excesses.

A chair, designed by Adolf Loos, from the Café Museum in Vienna.

And this proved shocking. Planning authorities in Vienna took out injunctions to stop work on Loos’ next major building, which was allowed to open only after the architect consented to some decoration: flower boxes on the upper stories.

However, this spare, clean, geometric, homogeneous style—in which “form” was content to “follow function”—caught on and became known in the 20th century as “modern architecture.”

And, if you look for it, you can find in this style the intention to make everything smooth and orderly, disciplined and logical, a goal shared by some of the loudest political movements of the left and the right in the 20th century, and by some of the most ambitious thinkers and artists: Bertrand Russell or Piet Mondrian, to choose relatively benign examples; or Lenin, who proved less benign.

But hippies were not much interested in straight lines. And they were the opposite of smooth, orderly and disciplined. They certainly would not have gone along with the ambitious, never-realized 1925 proposal by the modern architect Le Corbusier to replace the chaotic streets of Paris on the Right Bank with highways and grassy parkland, dotted with clean, regular, tall, housing-project-like modern buildings.

No, this was not your hippies’ modernism. Indeed, this modernism’s promulgators and partisans—including another Viennese, the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein—had they lived long enough might have found scruffy, trippy hippies distasteful.

Ah, but then there is the other version of modernism, which had appeared in Vienna almost six months before the Café Museum opened in the form of the Secession building. This was constructed as a center for a group of radical, forward-looking artists who had seceded from the staid Association of Austrian Artists.

And the Secession building was indeed far out: a white, temple-like structure that featured a construction on top with no discernable function: a giant, glittering blue and gold egg. Just below the egg, also in gold, was a dictum in German that can be translated as: “To Each Age its Art/To Art its Freedom.”

Designed by Josef Maria Olbrich, the Secession building introduced to the world a fanciful, free-flowing variety of modernism, which did indeed embody and champion a kind of freedom.

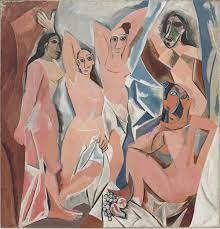

This would be the modernism that included the wildly animated, disjointed, dense, even excessive work of such writers as Woolf and Joyce and such artists as Pablo Picasso and Gustav Klint. Indeed, Klint was among the Secession artists in turn-of-the-century Vienna, and his 112-foot-long Beethoven Frieze would be displayed in the Secession building in 1902.

This was hippie kind of stuff.

Indeed, while I don’t think anything stronger than Burgundy or stout was involved, To the Lighthouse and Ulysses, Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, the Beethoven Frieze and even the Secession building itself, could certainly pass as psychedelic.

And whether ensconced on Astor Place or in the Haight, while in Burlington or Mendocino, while on or off acid or grass, the hippies had modernist—this kind of modernist—heads: trippy, jumpy, dreamy, infused with imagination. They came in colors: bright, swirling colors, like the Kesey bus.

And there was one more thing about this modernism: It helped gift the cultural world with the notion that art might, even must, repeatedly change phases, must repeatedly remake itself. And as “modern art” had jumped from Impressionism to Cubism to Abstract Expressionism to Surrealism to Pop Art, the Beatles jumped from pop to rock to psychedelic and then back to a simpler rock; and Bob Dylan jumped from folk to rock to country to Christian. And we all jumped, or skipped, at least part way along with them.

This modernist notion of moving on to the next thing also became very much a hippie thing.