The Most Powerful Ideas of All Time

What are the seven most transformative ideas humans have had—ever? Here is my list, counting down. What would you add or subtract? Is there a woman who—despite all the difficulty women have had getting heard—should have been included? Are there ideas from Asia that should have made this list?

7. Aristotle: “The actuality of life is thought”

This is the most abstract of the ideas on this list, but perhaps the most basic. It is the idea that the universe would lose much of its charm and meaning without creatures in it who think about it, who have ideas about it.

The universe, even life itself, is all just teeming, borderless, undifferentiated, meaningless potentiality until it becomes actualized through thought, until it becomes actuality by being thought.

It is, in other words, mostly the human mind—and words, human language—that gives the world its meaning as a collection of things distinguishable by more than their sweetness, threat or potential as a mate.

It is, in still other words, mostly human thought—and human words—that conclude, for example, that this is a sea, a strait, a bay or a gulf; that it is water, ocean, saltwater or brine; that it qualifies as deep or shallow, calm or choppy; or even as a current or an undertow or a tide.

And what we see and think is limited, more or less, to what we can name.

I first encountered Aristotle’s dictum—this quote—while reading his Metaphysics in a carrel in the library at Haverford College. That thought seemed so perfect, so lovely, that I felt compelled to write it on the desk. (Demonstrating, perhaps, that the actuality of a thought is becoming graffiti.)

Revisiting Aristotle’s dictum again I’m a little concerned by the context, which wanders indeed into metaphysical notions, with which I am not comfortable, and concludes—and this I did not write on the desk: “God is that actuality.”

Still, the notion that human thought actualizes the world is as good a place as any to begin a collection of our greatest ideas.

6. Jesus: “Do unto others as you would have others do to you”

This lovely and foundational moral principle appears in in the New Testament in both Matthew’s account of Jesus’ “Sermon on the Mount” and Luke’s account of Jesus’ “Sermon on the Plain.” It began being called “the Golden Rule” in early 17th-century England.

But it had previously appeared, in a negative formulation, in the Old Testament: "Whatever is hurtful to you, do not do to any other person."

And, centuries before Jesus’ birth, Confucius is said to have said: "What you do not want done to you, do not do to others.”

If morality begins anywhere, it begins here.

However, isn’t there an important fellow in the United States today who regularly and intentionally does to others what would infuriate him?

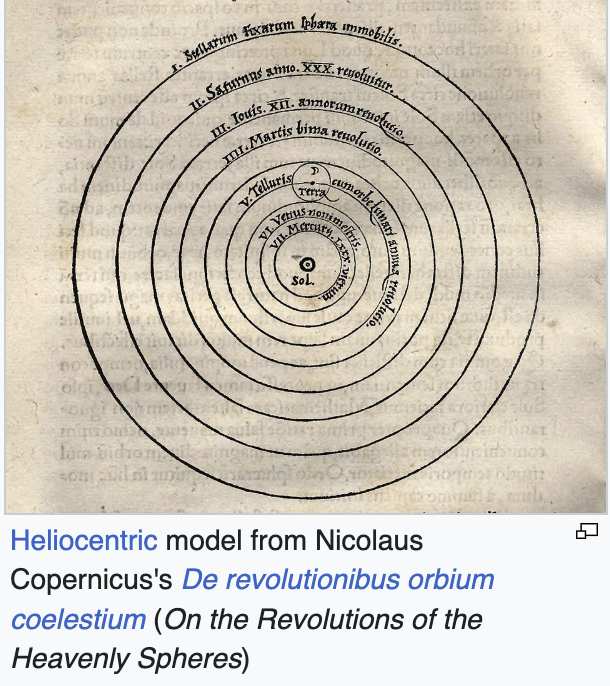

5. Nicolaus Copernicus: The earth revolves around the sun, rather than the sun, and the rest of the heavens, revolving around the earth

Yes, others—Aristarchus of Samos, in particular, in the 3rd century BCE—had proposed a heliocentric solar system earlier, in more tolerant societies.

But it was Copernicus, writing in Christian Europe shortly after the invention of the printing press, who finally succeeded in overturning millennia of common sense and religious dogma, by enabling us to understand that, despite all appearances, we are not at the center of things.

And, once Copernicus got up the nerve to publish his book, De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres), and as its message began, over the centuries to sink in, the sky began to look different and our existence more random.

4. Charles Darwin: The earth’s population of plants and animals has evolved and continues to evolve over time due to natural selection

Some ancient Greeks did, to be fair, have inklings that creatures might change. But before Darwin most thought that all species—"once created”—had always been around.

Darwin removed the “once”: The natural world, he realized and demonstrated, is and always has been in flux—with species, Homo sapiens among them, coming and transforming, according to the rules of “natural selection,” and maybe going.

Darwin’ also removed the “created,” and probably did as much to diminish the role of religious dogma—and Adam and Eve, and Noah’s ark—in understanding history and science as has anyone ever.

This idea entirely transformed our understanding of life on earth and our relationship to it. And we would never again look at a monkey in the same way.

3. Rousseau, Voltaire and Diderot: “Liberty, equality, fraternity”

There was a revolution in each of these three words—not only an assault upon monarchy but the end of inherited orders, ranks, and privileges and a call for us to recognize our own brotherhood.

“All men are created equal”—despite not being true and, outrageously, leaving out women, sisters—was pretty damn powerful too.

Yes, we all have different abilities and different resources and different luck. But shouldn’t we all—and, over time, that “all” would finally grow to include different races and different genders and different sexual preferences—be free to pursue happiness and have equal rights.

A new politics—one currently under threat in many parts of the world, including our own—flowed from these 18th-century words.

None of the three men I have credited here lived to see the French Revolution or participated in the coining of the slogan I quote. But they each played major roles in championing its goals.

2. Francis Bacon: Knowledge should follow from experiment not authority

Before the 17th century, much of what passed for knowledge was inherited—handed down from Scripture, Aristotle, physicians with theories about humors, or philosophers who preferred tidy categories to messy evidence. Then came a startlingly subversive idea: maybe we should actually check whether the world works the way we think, or would like to think, it works.

Francis Bacon, writing in the early 1600s, didn’t invent experimentation—humans have been boiling, smashing, measuring, and fermenting things forever. What Bacon did was something larger: he argued that knowledge itself must be grounded in systematic observation, experiment, and the slow accumulation of evidence—not in authority or tradition. His Novum Organum is the closest thing we have to an origin document for the idea that truth must be tested; that hypotheses must earn their keep; that philosophers should get their boots muddy.

Galileo, a contemporary, showed what this new idea looked like in practice. Boyle and Newton built the laboratory and the mathematical scaffolding around it. But the conceptual leap—the notion that belief must bow to evidence—belongs mostly to Bacon.

This may sound obvious now—grade-school obvious—but it wasn’t then. It was revolutionary. And, alas, it is still not obvious in many places and in billions of minds today.

(The wording of this thought owes much to ChatGPT 5.)

1. The Babylonians and Thales: That mathematics can be used to understand the behavior of objects in the heavens and on earth

The Babylonians can be credited with the realization that detailed numerical records could be kept not only of amounts of sheep and grain but of the movement of planets. They employed a base-60 (to be distinguished from our base-10) number system.

About that time and probably borrowing some of this math, Thales is said, by Herodotus, to have predicted the solar eclipse of 585 BCE. An event that—more even than the explosion of the first atomic bomb at Los Alamos—might qualify as the most dramatic confirmation of a human idea ever.

Galileo, who believed the universe is "written in the language of mathematics," used mathematics—a mathematics that had been improved by the addition of the zero in India a thousand years earlier—to explore the behavior of falling bodies and heavenly bodies.

And, of course, Isaac Newton used mathematics, in particular the calculus he invented, to discover the laws of gravity that governed the behavior of falling bodies on earth and the planets in the sky.

Einstein would employ a more complicated mathematics, now called “tensor calculus,” to calculate how gravity curves space-time.

The physicist Eugene Wigner has marveled at “the unreasonable effectiveness of mathematics" as a tool for understanding the universe.

No idea has illuminated more of the universe than mathematics.