This Won’t Be Humankind’s First “Intelligence Explosion”

We are, we are told, living on the cusp of an “intelligence explosion,” which will, the tech savants inform us, either rain wisdom down upon us or kill us all.

I’ll focus, here, on the more pleasant alternative.

And as a media historian, I might be able to add some perspective. Which might prove useful. For this “explosion” is starting to resemble, to mix metaphors, a giant snowball rolling downhill.

You have undoubtedly noticed that our Dr. Frankensteins have invented computer programs—artificial intelligences—that are already more thoughtful than you and, increasingly, more eloquent than you. These computer programs have access to all the world’s information, and increasingly apply what surely appear to be smarts—very high-level smarts—to it.

So computers have not only figured out how proteins are folded and memorized all the information on the internet; they can write in the manner of Shakespeare or Joyce or Dr. Suess. They can also draw in the style of Leonardo—though a thousand times faster. And chess matches between silicon-them and fleshy-us are already no contest.

The snowball has already grown very large indeed.

What’s next? Well, cures for Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s would certainly be nice.

But the biggie will apparently be when computers, in their ever-increasing wisdom, themselves figure out how to design and program computers that are significantly smarter than are computers designed and programed by mere suck-at-chess, barely-able-to-sustain-iambic-pentameter humans. Then the snowball will expand as it rolls—exponentially.

Gosh!

Whoa!

But also: Oy vey!

And we might be tempted to add: Incomprehensible!

But I might have a wee bit to contribute to the ongoing struggle to comprehend.

For, I maintain, such a dramatic leap in astuteness is not unprecedented. This ain’t humankind’s first “intelligence explosion.”

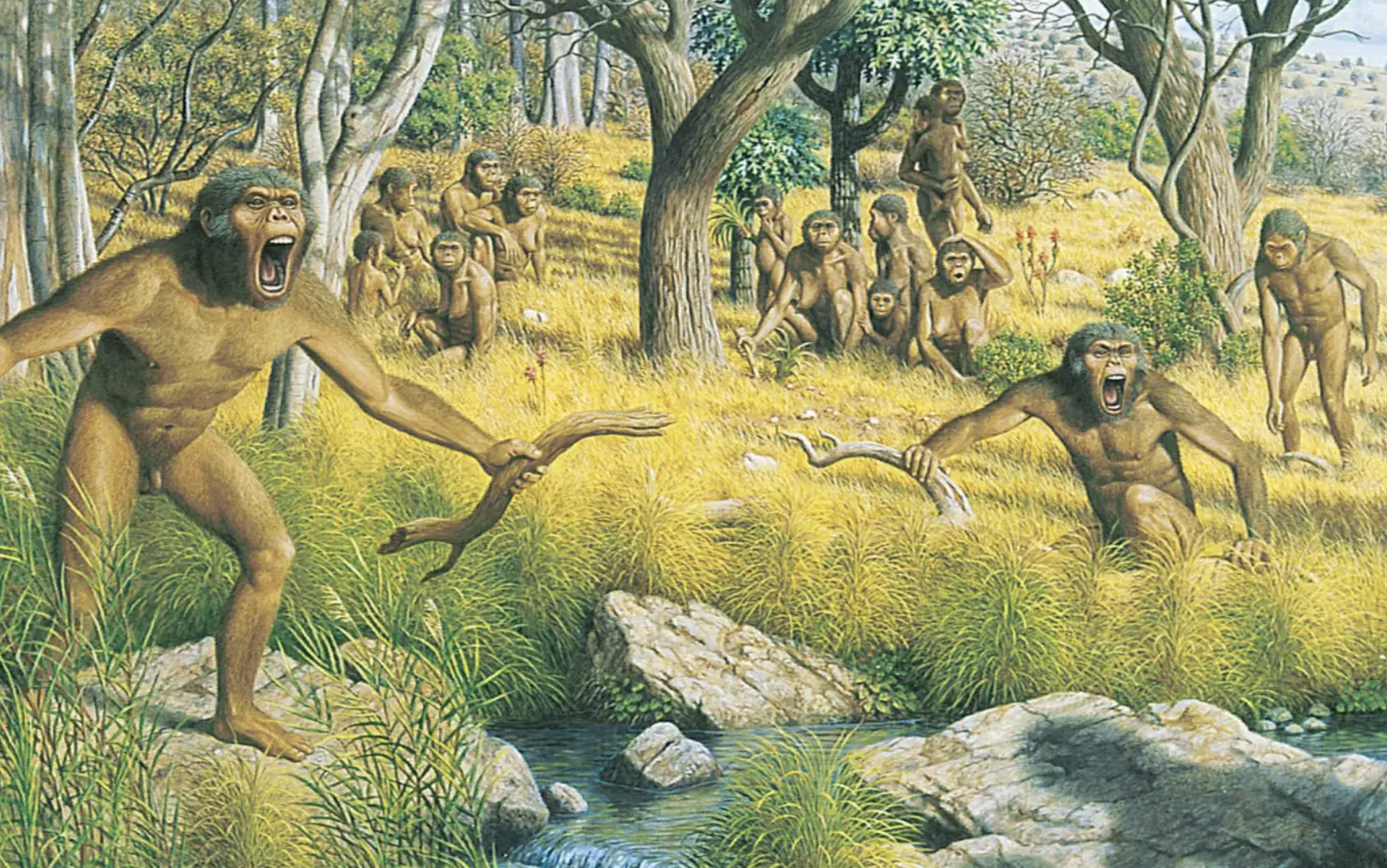

Language: the first intelligence explosion

If you want to know why humans keep gorillas in cages, not the other way around, this is where you start: with words and syntax. Their arrival probably still qualifies as the crucial step in the development of humans’ outsize smarts. Indeed, as I write, language probably still qualifies as the greatest accelerator of intelligence yet seen in our little corner of the universe.

And, if our particular variety of primate had not evolved among the tall grasses of Africa, language likely would not have happened. For language followed from humans needing to stand tall, so they could spot predators and game on the savannah.

Homo erectus—a variety of human dating back about 1.6 million years—therefore evolved to the point where they stood and walked fully erect on just their feet. That freed their hands to evolve so that they could tear apart food; which freed their mouths to make distinct and complex sounds. There is evidence that Homo erectus had some form of language.

We Homo sapiens go back only a few hundred thousand years. But we always were bipedal. And we may always have been, to our considerable advantage, rather chatty.

You can loosely coordinate a hunt, as lions demonstrate, without language. Chimps, our cousins, use gestures to work out things like who is going to groom whom. We don’t really know how far dolphins or whales get in communicating. And bees do have their way-to-the-pollen dances.

However, there is no evidence that any still-extant species besides our own can communicate abstract and complex ideas and that is because we are the only species around with a language—one shaped by mouths and a vocal system devoted in large part for that task.

Without language you can’t create a myth. You can’t create, let alone memorize, an epic. You probably can’t conceptualize and analyze. Words—names for things but also verbs, adjectives, adverbs and conjunctions—plus their arrangement with grammar—are magic.

It seems fair to say, that most of the unique intelligence humans developed follows from spoken language.

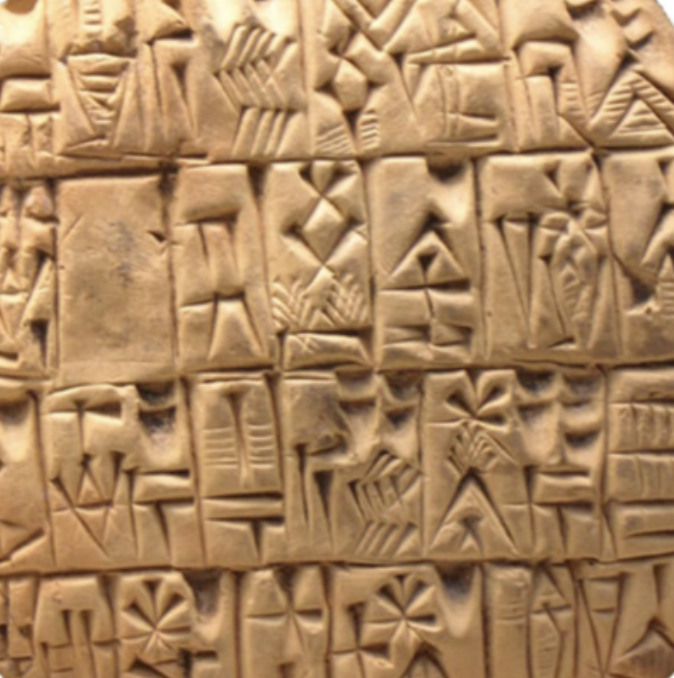

Writing: the second intelligence explosion

Humans appear to have been telling tales for many tens of thousands, maybe even hundreds of thousands of years. But they—actually some small few of them—only began to write, to make words into objects, about five-thousand years ago. First in Mesopotamia.

Don’t underestimate how large a leap it was to transform something as airy and ephemeral as a spoken word into something as permanent as a symbol on a piece of clay. Transubstantiation of a sort.

A large part of the magic was in the auxiliary memory writing providing—the recording, the preservation, of tales, dates, occurrences. ‘Twas writing stuff down and keeping it around which started the long, and to some extent still ongoing, process of replacing myth and legend with history.

But the real magic of writing was in making words into objects that could, for the first time, be rearranged, compared, examined and reexamined; that could be fashioned into new ideas.

Writing enabled Plato to write a dialogue arguing that writing would never replace a teacher’s instruction. And that dialogue—Plato’s actual argument, in Plato’s own words—could be read, over the centuries, by students around the world.

Writing helped Aristotle manipulate words with sufficient dexterity to work out a distinction between “actuality” and “potentiality”—a mind-bending distinction students, myself included, would puzzle over for more than two millennia.

And almost all that intelligence was copied and recopied and had been collected for a time—made available, pooled together—in a library in Alexandria, which was, perhaps, ground zero of writing’s intelligence explosion.

And it initiated chain reactions. One scroll, one manuscript, one codex inspired a few others and those each inspired a few others. That seems pretty damn exponential right there.

Oh, and Werner Heisenberg said he made use of Aristotle’s concept of potentiality and actuality when inventing quantum mechanics. So the intelligence made possible by writing continues to explode today.

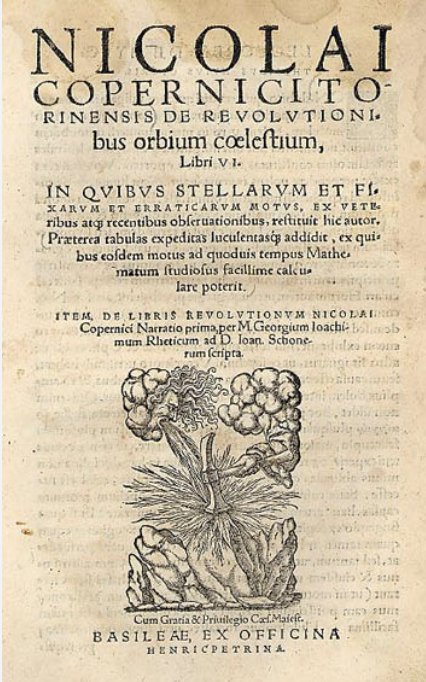

Printing: the third information explosion

And more so—much more so—with the printing press.

Nicolaus Copernicus was born only a couple of decades after the invention of the European letter press by Johannes Gutenberg in Mainz, Germany, in about 1440, but Copernicus was able to make much use of printed information.

Copernicus found of particular value the Epitome in Almagestum Ptolemei, a revised and expanded account of Ptolemy’s earth-centered view of the cosmos printed in Venice in 1496. Copernicus secured a copy, probably that same year, while a student in Bologna.

The printing press had made it dramatically easier to obtain copies of such texts. And it dramatically diminished the possibility that errors had been added to those copies in the process of making copies. Copernicus took full advantage of the more reliable data in that book—much of which he used to prove Ptolemy wrong and demonstrate that when it came to the sun and the earth the movement was vice versa.

Copernicus only dared to print his own revolutionary book, De revolutionibus orbium coelestium, right before he died. But it was printed and reprinted by the dozens, by the hundreds.

Galileo read Copernicus’ book and was profoundly influenced by it. And Kepler read and loved Galileo’s account of his telescopic observations. (The telescope having unleashed a bit of an intelligence explosion of its own.) And Newton read and loved Kepler’s book. And Voltaire’s lover, Émilie du Châtelet, turned him on to Newton.

And, a few centuries after the invention of the printing press, a gaggle of thinkers in Paris including Voltaire, and led by Denis Diderot, decided to gather “all the knowledge scattered on the surface of the earth” in a multi-volume printed encyclopedia, which included a chapter on Newton and a somewhat-disguised attack on the divine right of kings.

And Thomas Jefferson owned a copy of Diderot’s Encyclopédie.

Nonetheless, Tolstoy complained, near the end of War and Peace, that the printing press was “ignorance’s weapon.” And, in truth, a lot of crap did get printed. But War and Peace got printed and translated, along with a lot of political ideas and science.

And Albert Einstein read and loved Newton’s book.

So, thanks to the printing press, the earth was no longer at the center of the universe and gravity held the solar system together and a great experiment in democracy was launched and space-time was curved.

Electronics: a fourth Intelligence explosion?

I suspect—given these time spans—that it may still be a little too early for us to get a handle on the accomplishments of the radio, film and TV, let alone the Internet and communication satellites.

After all, it had taken a century and a half before the unique packages of knowledge created by the printing press—the newspaper and the novel—had appeared.

Certainly, knowledge has spread electronically. It is great that doctors in Uganda now have access to most of the same medical information as doctors in the United States. And the fact that we can access information from and stay in touch with more or less anyone, anywhere, at any time is, for those of us who immigrated into this century from the previous one, not only reassuring but pretty damn cool.

However, the question is whether intelligence has been given a significant boost by the development of electronic (and photographic) forms of communication?

We certainly have figured out some things. We are, for example, learning—rather late, alas—how to power things without burning stuff.

But social media, sigh, certainly seem so far like a net negative for intelligence.

Maybe the intelligence explosion hinted at with electronic media will arrive only with AI.

And AI—although many of us are beginning to find it useful—is still very, very young.

* * *

Look, I’m not going to pretend there haven’t been side effects—including wars and repression—that flowed from all these other intelligence explosions. Indeed, language, writing, print, TV and now social media may have made us neurotic as well as smart.

Pollutions released by exploding intelligence—in the form of coal-burning and then oil burning—have poisoned air and raised the temperature of the planet. And Einstein’s revelations about the huge amounts of E locked up inside atoms, may have been part of the first knowledge explosion that truly had/has the potential to kill us all.

But, all and all, I think our experience with exploding intelligence has been positive. Lots of wrong turns and dead ends, to be sure. Personally, I could have done without Mein Kampf, the National Enquirer and smoke from Canadian wildfires. Still, it is hard not to conclude that knowing more is better than knowing less. Certainly, there’s not much to be said for idiocy vortices like the one that has currently settled over the city of Washington.

So, with the caveat that it would suck if all the humans got killed, I’ll take an explosion of intelligence—organic or artificial—over stupidity any day.

For a discussion of the current “intelligence explosion” and its dangers, click here.

For “So, You Think You’ve Seen AI,” click here.

For a consideration of the “doom” scenario for AI development, click here.

For a video, made a few years ago, comparing AI with HI—human intelligence—click here.