The Ten Biggest Changes in the World in Our Lifetimes

The world today is very different from the world into which we were born. It has gone through plenty of ch… ch… changes, as have we all.

Many of those global changes in the period since the end of World War II have been dramatic, some so overwhelming they are difficult to comprehend. Nevertheless, here at Writing About Our Generation we are going to try and do some comprehending.

So, after our ranking the biggest changes in the United States in our lifetime, here is how we rank, in ascending order, the 10 most significant global changes of the last 75 or so years.

Agree? Disagree? Have a ranking of your own? Let us know in the comments below or by emailing here.

10. The Growth of Islam and Religious Fundamentalism

Demonstration against the Shah in Iran.

In 1950 about one in three people in the world were Christian and only one in eight Islamic. The number of Christians has grown, but not as fast as the world’s population. However, the proportion of the world’s population that is Islamic has doubled. It is about one in four in 2025.

And, beginning in the 1970s, a number of Arab and devoutly Islamic countries, mostly located on the Persian Gulf, became very, very rich by selling oil.

Growth in Islam’s size and influence was often accompanied, particularly in the final decades of the 20th century and the initial years of the 21st, by an increasing resistance to quasi-colonial rule accompanied by an increasing religious fervor.

· In 1979, an Islamic revolution in Iran overthrew the US-supported Shah.

· Islamic fighters held off the Soviet Union in Afghanistan from 1979 to 1989.

· Then, after Islamic terrorists succeeded in bringing down the two giant World Trade Center buildings, and killing almost 3,000 people in New York City in 2001, Islamic fighters held off the United States in Afghanistan from 2001 until 2021.

Religious fervor also arose in fundamentalist Christianity, which became more of a political force in these decades in the United States. And Israel shifted from a left-leaning Jewish country of communal kibbutzes to an increasingly right-wing, orthodox country unwilling to allow the Palestinians who lived in the territory it controlled basic rights.

9. The Rise—and Maybe Fall—of American Dominance

First McDonald’s in the Soviet Union.

At the end of the second world war, Europe and much of Asia lay in ruins. Many countries, including the Soviet Union, had suffered millions of deaths and unthinkable destruction. China was in the midst of revolutionary turmoil.

However, the United States, protected by two vast oceans from much of the devastation of the two world wars, was strong, confident, militarily superior (the “arsenal of democracy”) and economically voracious.

The United States became the world’s largest creditor nation and our currency became the basis of the new global financial system. The U.S. was for a time the only country with nuclear weapons. But even after other nations developed those arms, America had—and continued to have—the world’s strongest military, with bases across Europe, Asia and the Pacific.

The “soft power” of the United States may have been even more significant, as globalization intensified, and the country’s politics, culture, businesses and language spread throughout the world. With McDonald’s, rock ’n’ roll, Hollywood and a commitment to foreign aid, the U.S. had become “the indispensable country,” the world’s unquestioned “superpower”—particularly after the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991.

And that lasted through the second half of the 20th century and well into the 21st century. It lasted despite a series of foolish and failed military adventures: in Vietnam, in Iraq, in Afghanistan.

But now, after three-quarters of a century, that dominance may be waning.

China is fast becoming a countervailing military, economic, scientific and cultural force. And under a President Trump, who sees the rest of the world as full of adversaries, U.S. influence—from the strength of its dollar to the benefits of its foreign aid—has diminished some and may diminish more.

As political theorists Robert O. Keohane and Joseph S. Nye, Jr. have recently written in “The End of the Long American Century,” “Trump’s current … policy … weakens the United States and accelerates the erosion of the international order that since World War II has served so many countries well—most of all, the United States.”

8. Global migration explodes

Migrants in the Mediterranean Sea.

Many humans first successfully migrated out of Africa about 60,000 years ago. And humans have been moving from continent to continent, from area to area, then from nation to nation, ever since. But the past 75 years or so have seen a leap in global migration—and recently, a significant backlash against the migrants.

A surge in global resettlement was driven first by the devastation caused by the Second World War. Then some people moved to escape oppression. Some moved to escape new military conflicts or political instability. But mostly people moved for economic opportunity: from rural areas to big cities, which usually offered more and better paying jobs. They moved globally from the east to the west and from the south to the north.

People moved much more quickly and easily with the rise of air travel. And the arrival of the internet meant they could stay in touch with loved ones even after they moved.

The number of international migrants has grown, from 77 million in 1960 to 281 million in 2020—including 108 million refugees and asylum seekers.

Climate change seems likely to spur new migrations, away from desertification and droughts, or away from rising sea levels and floods, or away from intensifying heat and storms.

While immigration has often filled labor shortages and contributed to economic growth in richer countries, many in those richer nations—the U.S. and western Europe in particular—are becoming increasingly resentful of influxes of immigrants, particularly migrants from the global south.

Indeed, the flow of immigrants has contributed to the rise of right-wing, nationalist parties in the Europe and the United States.

7. Women Leave the Home

Simone de Beauvoir.

For much of the history of civilization women were mostly expected to raise the children and keep the home functioning. If they worked, they were often limited to low-wage jobs.

In many countries, women had few legal protections, limited property rights and no legal recourse against gender-based violence. Studies have concluded that women had less than half the legal rights of men immediately after World War II.

However, when men went off to fight that war, women were asked to do much of the work the men had left behind. After the war, many of those women wanted to continue working outside the home. And many families benefited from or required the dual income.

Meanwhile, washing machines, dryers, vacuum cleaners and dishwashers took over some of the work women had been doing at home; the growing service economy provided substantial jobs for women outside the home; and the women’s movement of the 1970s overturned the stereotypes that had limited their choice in jobs.

In addition, most countries—but not all; there are still a number, particularly in the Islamic world, that continue to treat women as second-class citizens—have enacted laws granting women rights to vote, own property, work and access healthcare and education.

Indeed, a dramatic increase in women’s ability to pursue an education has been crucial. Girls often had had limited access to schooling, especially beyond the primary level. However, today in many parts of the world women now outnumber men in colleges and universities.

Indeed, more women now are active in nearly every sector of the economy, from technology and finance to construction and agriculture, and women are increasingly represented in leadership roles in business, industry and government. Women now make up about a quarter of national parliaments worldwide, up from about 2 percent in 1950.

Yet women are still treated as second-class citizens and subject to violence in some countries, particularly in the Islamic world.

And, with both parents now often working, the strains on family life have, to be sure, intensified, with a concomitant decline, in richer countries, in the number of couples willing to undertake having children.

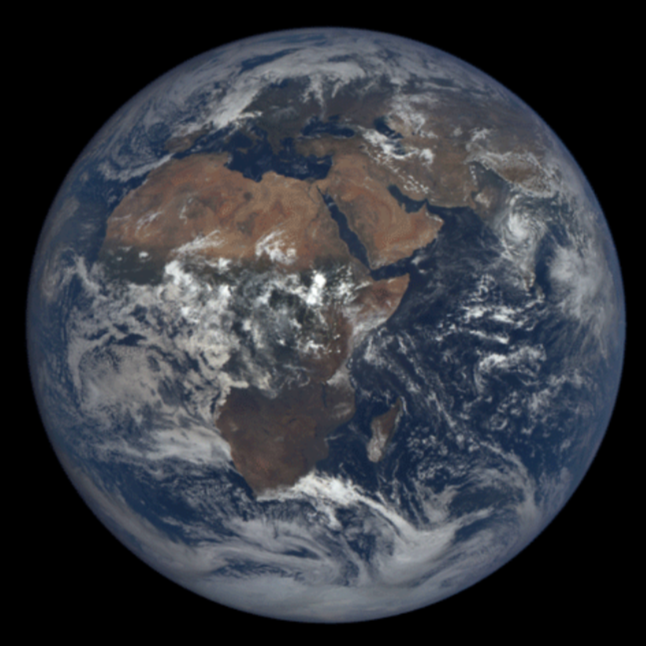

6. The Despoiling of the Planet

Humans have been defacing the planet at least since the invention of agriculture 12,000 years ago—cutting down trees, starting fires, clearing land, building on what had been pristine. That destruction gathered speed with the Industrial Revolution, more than 200 years ago.

Burning coal or low-grade oil could turn the air black. Pollutants and garbage filled many rivers and streams. Internal combustion engines fouled the air behind them.

A few pollution controls—particularly on cars and trucks—have helped clear the air a bit. Some of the thoughtlessly tossed trash has been cleaned up—at least in the wealthier countries. But much damage has been done. And much continues to get worse.

We have polluted the oceans with garbage and microplastics. We have deforested the Amazon and other natural habitats, destroying an average of 12 million hectares of forests annually. Human activities have caused the extinction of dozens of species.

Perhaps most worrisome of all has been an exponential increase in greenhouse gas emissions thanks to ongoing and now worldwide industrialization and the skyrocketing demand for more fossil fuel to power a growing number of cars, motorbikes, planes and ships. Over just the last decade carbon dioxide in the atmosphere rose nearly 200 times faster than during natural cycles. Those gases have been the prime cause of extensive global climate change, which may threaten the future of many kinds of life on this planet, perhaps including human life.

The last decade was the hottest on record, with 2024 reaching +1.6°C above pre-industrial levels. Which means the polar ice caps are melting, sea levels are rising, storms have become more destructive and more parts of our earth are becoming uninhabitable. More than 100,000 heat-related deaths were reported in Europe over the last three years, after negligible numbers in preceding decades.

A growing awareness of what we are doing to the earth has led to attempts to at least slow global warming—and so there have been increases in alternative sources of power such as solar and wind, and governmental agreements like the Kyoto Protocol and the Paris Accords.

But stated goals haven’t been reached and one of the major contributors to global warming—the United States—has now withdrawn from such international agreements.

5. Globalization Invigorates but Also Homogenizes

The Rolling Stones on Ed Sullivan.

The world has gotten, in our lifetimes, all mixed up.

In many ways that has been great. American rock and roll, for instance, which owed so much to European and particularly African music traditions, then traveled in the other direction across the ocean: to Britain, for example—from which it then bounced back across the ocean and circled the planet in the form of the Beatles and the Rolling Stones.

The culinary world has benefited from similar and ongoing mixings. So have other art forms: painting, cinema, theater. And the global economy has benefited greatly from such exchanges across borders and oceans. More than 50 countries now contribute to the making of Apple’s iPhone. The Trump’s administration’s clumsy efforts to interfere with such exchanges have served to highlight how ubiquitous they are.

Such international economic partnerships have been facilitated by container ships and jumbo jets, as well as by satellite communications and our digital World Wide Web, which make communication and coordination from continent to continent easy. They also make it possible for artists, chefs, musicians and all of us around the world to learn from each other.

And English has given many of the world’s peoples a common second language, with which they might more easily communicate.

But there is another way to look at all this global mixing. Think of a paint can into which has been poured a bunch of bright colors. When you begin stirring it, you get a lovely rainbow of colors. But stir enough and all you end up with is a dull brown.

Might Europe become less European, Asia less Asian and Africa less African as we continue to stir the paint can?

The number of languages in the world has been declining sharply. Cultural idiosyncrasies—the French beret, the English tea break—are disappearing. In some places, old ways of doing things are being lost.

Is it possible we will get so globalized, so homogenized, that we will run out of alternate perspectives, new ways of doing things, new ideas?

4. The End of Colonialism

Nehru and Gandhi.

Countries, or wannabe countries, don’t like being ruled by other countries. That was true in America in 1776. It was even more true in the second half of the 20th century when, for the most part, the rulers were white Europeans and the ruled were not.

Freedom from colonial rule spread rapidly after the Second World War: because the war had exhausted the colonial powers and because the colonized nations increasingly were developing an educated and freedom-craving middle class. Freedom and liberty, encouraged by the new United Nations, were very much in the air.

And so nation after nation—sometimes with difficulty, sometimes more easily—broke free of the colonial yoke: India in 1947. Egypt in 1952. Vietnam in 1954. Tunisia and Morocco in 1956. Seventeen African countries achieved independence in one year, 1960, alone. Successful liberation movements continued throughout the 1960s and 1970s.

For the first time, people in formally colonized territories had the chance to govern themselves, build their own institutions and define their own futures, politically and economically.

Some countries did it well, and became thriving democracies. But independence didn’t always bring national success, prosperity or peace and freedom.

Colonial borders had often lumped together rival groups or split communities—leading, after liberation, to civil wars, coups and ethnic conflicts. Some regions, such as the Middle East, Southeast Asia and Central Africa, became Cold War battlegrounds, with superpowers backing different factions and some newly independent states replacing their colonial overlords with harsh home-grown dictatorships or theocracies.

But those dozens of countries that became independent states at least had a chance to build something for themselves. And the Western powers had to begin to share military and economic control of the world with them.

3. Technology Remakes the World

Uganda 2025.

Commercial television—moving images along with sound transmitted by radio waves—began in the United States right after the end of World War II. By the mid-1950s half of all American homes had a TV. The other half and most of the rest of the world would soon follow. And the parade of new technologies that would captivate us was underway. It included:

The long-playing record introduced by Columbia Records in 1948;

The transistor radio, beginning with the expensive Regency TR-1 in 1954;

The personal computer, as created most successfully by Apple in 1977 and IBM in 1981;

The World Wide Web, invented by Tim Berners-Lee in the early 1990s—allowing all those computers to share and converse;

The cell phone—dating back perhaps to Nokia’s in 1992—which was a “leap technology”: people in areas too rural to reach with telephone wires suddenly were connected;

Jeff Bezos’ Amazon.com, which initially just sold books, in 1994;

Apple’s iPhone in 2007.

And, as most of the above improved, information—on screen then online—was everywhere; up-to-date medical information was available everywhere, humor was everywhere; entertainment was everywhere; porn was everywhere. We were connected with everyone and everything . . . and maybe, as a consequence, less connected to the people we physically encountered.

For these technologies subtracted some as they added much. Soon enough the telegram, the letter, the postcard, the home phone, the secretary, the local newspaper, the shops downtown and even the boredom of staying home alone itself, were on their way to extinction.

And the technological assault of the past 75 years, by making being alone less boring, has also put under threat back-fence conversations, coffee klatches, card games and chitchat at the grocery store.

Indeed, it is threatening, maybe, our inclination to leave the house, to hang out, to build friendships, to make romance.

2. Life Expectancy and Population Boom

Global life expectancy has risen from around 46 years in 1950 to approximately 73 years today, thanks to advances in medicine and public health and living standards.

Although it has not often made headlines, this means there has been a sharp reduction in the great tragedy—for individuals and their loved ones—of premature death, particularly the once common death of children.

And this profound change has given people around the world additional decades to love, to work, to socialize, to create, to explore and to think.

It has also contributed to a tremendous acceleration in the growth of the number of humans on this planet—a growth rate highest in the early 1960s but still much higher today than in earlier eras.

There were 2.5 billion people on Earth in 1950. There are now 8.2 billion—an increase of 5.7 billion humans since 1950.

This unprecedented population boom has been felt in all the changes discussed above. There are now 228-percent more people expelling toxins into the air than there were in 1950; 228-percent more people who may choose to emigrate to somewhere where prospects are brighter; and also 228-percent more people from whom might arise the next great invention.

Additional cures for human diseases are likely to be found, especially with the help of artificial intelligence. That should further extend human lives.

However, this accelerated growth in the human population of the earth is not expected to continue. A decline in marriage rates and in couples desiring to have multiple or any children has already made sustaining population a problem in some first-world countries and that problem seems likely to spread to other countries as prosperity spreads.

1. A Sharp Decline in Extreme Poverty

Uganda 2025.

In 1950, 53 percent of the world’s population lived in extreme poverty, defined as unable to meet basic needs including minimal nutrition and adequately heated shelter. In 1975, 36 percent of the world’s population still lived in extreme poverty. By 2018, despite the rapid increase in the world’s population discussed above, the percent of that population living in extreme poverty, so defined, had fallen to 10 percent.

It is hard to argue that any other change during our lifetimes has affected so many people so dramatically.

Huge improvements in agricultural methods have made it possible to feed many, many more mouths. And many, many more families can now afford proper nutrition.

That 10 percent of humans (hundreds and hundreds of millions of people) still live in extreme poverty—in a world that includes many billionaires—remains shameful. And some of of the poverty found in the world in the 19th century and into the 20th century can undoubtedly be attributed to a rapacious and unchecked capitalism that sometimes paid workers below subsistence wages.

Yet it seems clear that a shift away from Communism and socialism at the end of the 20th century toward economies based more on regulated free enterprise, even with all the inequities that can bring, has contributed to increased prosperity for much of humankind.