Cowboys, Native Americans and the Hippies

Click for the introduction to this series: “The Roots of the Hippie Idea.”

“Whitman and Thoreau and the Hippies.”

Cowboys, Native Americans and the Hippies

Why I’m Still a Hippie (at 73)

In 1959, a large majority of the kids who would become the hippie generation could be found staring at a new and exciting presence in their family’s living room: a television set. And, in 1959, seven of the ten most watched television programs in the United States featured cowboys.

Which was odd, since in reality cowboy work—mostly sitting on the back of a horse and watching or moving herds of cattle—was dirty, boring, underpaid work.

But a romantic view of the cowboy, as a brave, gun-toting individualistic outdoorsman, had taken hold in a country increasingly populated by paper-pushing indoors men and mostly still-stuck-at-home indoors women, in a country eating balanced meals of hamburgers, mashed potatoes and frozen peas.

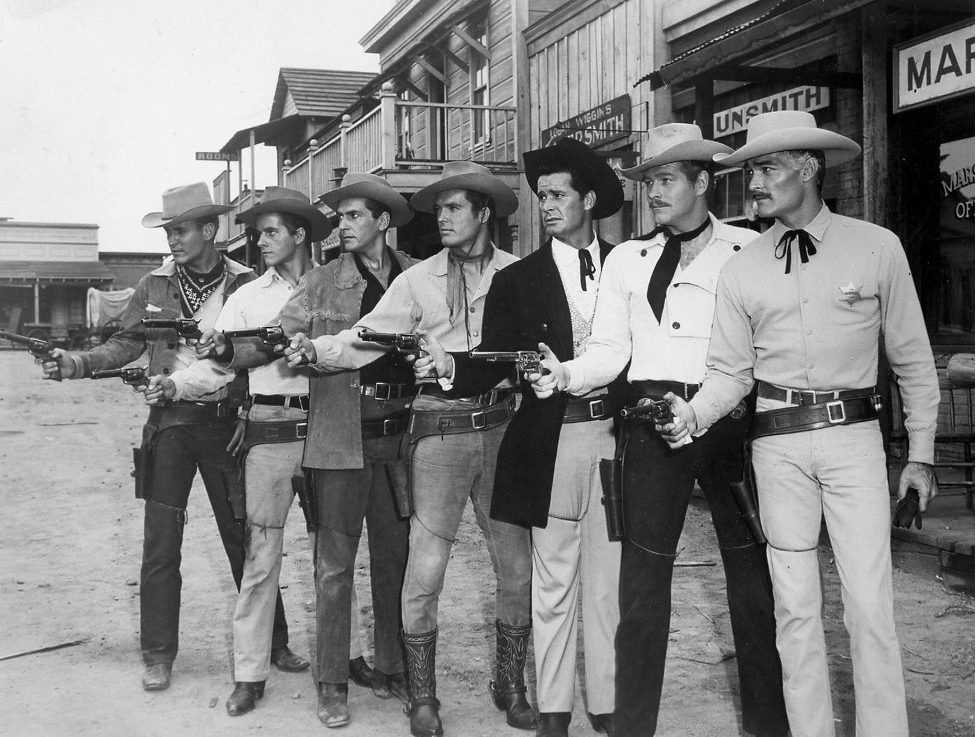

Here is a photograph of the cowboy TV stars from one Hollywood studio, Warner Bros., in 1959:

Is it possible to spot embryonic hippiedom in these eight TV cowboys in 1959—perhaps the peak of clean-cut, cookie-cutter conformism? Well, hippies, after all, did have a predilection for boots and bandanas and, certainly, for jeans.

But, more significantly, cowboys displayed, or at least feigned, a restless and rugged, don’t-fence-me-in, adventurous spirit that attracted us perhaps overly comfortable middle-class, suburban kids in what had become far and away the richest country on earth.

After the Second World War ended and more and more prairies were becoming suburban developments and fewer and fewer horses could be seen on urban streets, the romance of the cowboy grew. Indeed, it grew roughly in reverse proportion to the prevalence of the cowboy. (The old absence-heart-grow-fonder thing.)

Mom and dad were looking for comfort after the war, looking to stay put and sink roots in a suburb where the houses were all variations on a theme. Three bedrooms and a garage—plus a Manhattan or a Sloe Gin Fizz every evening—were just reward for having won that war.

Sister and brother, however, were looking to explore new trails. Cowboys appeared to have blazed some.

Cowboys did not have lawns or driveways. They weren’t able to sit in a living room watching themselves because they didn’t have TVs. Milk not only was not delivered, it did not seem to exist. Cowboys—hear this mom!—did not drink milk.

Yeah, they fought, even shot and were shot at, which was exciting, which we played at: cowboys and, uh, “Indians.”

But, perhaps of more significance, cowboys rode—into and out of town or the next town or the town after that. They sometimes rode all night. They carried a bed roll with them. And it was a tentative sleep they slept—when they stopped and started a fire for coffee in metal cups and unrolled their roll, stripping down to their long johns, with their horse tied up next to them and a pistol by their side. Who knew what bad guys might arrive and require killing? Who knew what frontier ladies in distress might require rescuing?

Yes, cowboying was outdoor work. With Americans increasingly ensconced in suburbs and offices, having a tan—once mostly a signifier of manual labor—began to seem more fashionable and the open range more attractive.

That romanization of the cowboy had actually begun a few wars earlier, in 1883 with Buffalo Bill Cody’s “Wild West” show, a show that toured the United States for 30 years. And, unlike those 1960s TV cowboys, Buffalo Bill, who lived in a less conformist time, might have fit right in in Haight-Asbury in 1967:

Besides this random San Francisco dude, for example:

Or even with this not-random dude from Hibbing, Minnesota:

The romanization of the cowboys may have peaked with Gunsmoke, the most watched television program in the United States from 1957 through 1961 and then with Bonanza, which held that title from 1964 through 1967. (Irony-loving kids like me, however, preferred Maverick.)

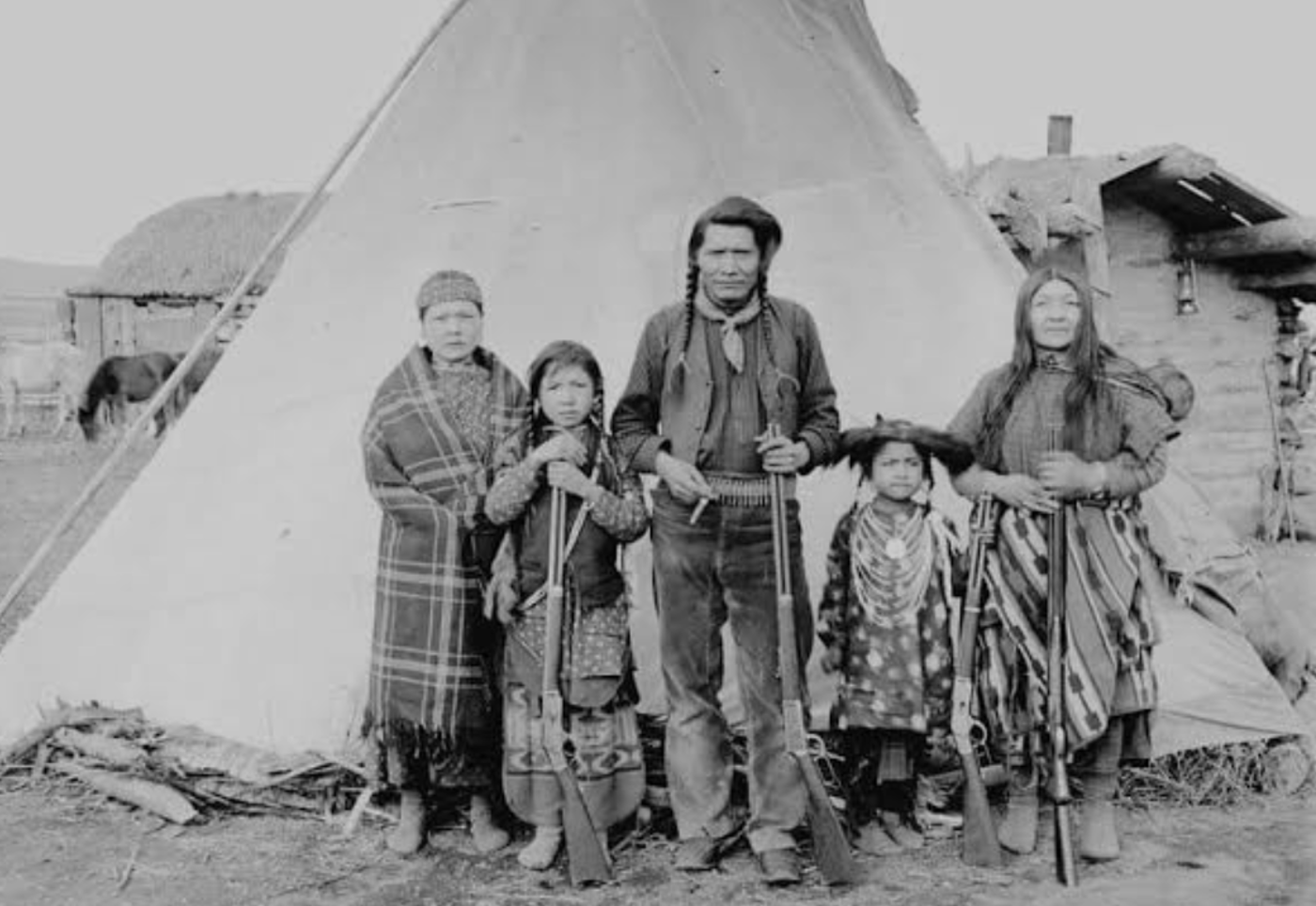

Romanticizing “Indians”—as Native Americans, in one of history’s greatest geographical errors, were still called back in the 1960s—made considerably more sense, since they actually lived close to nature and communally.

And that native-American influence may even have exceeded that of cowboys, when it came to hippie dress, even hippie behaviors:

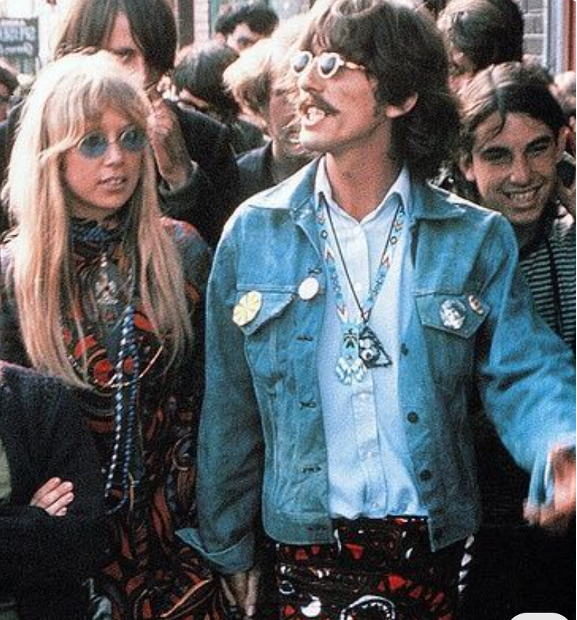

Here are George and Pattie rocking Native American and cowboy (as well as South Asian) accessories and threads.

The big-hatted, saddle-up cowboy spirit survived into the 21st century more in the south and in rural areas than in the northern and western cities and suburbs to which most of the hippies migrated.

But some of us still honor—in our way—this line of hippie ancestry.