Jeans Part I: Dressing Down

A lot of us believe something significant happened to culture in the 1960s and 1970s, when most of us were coming of age.

Part of that something—and the subject of this article—was a rejection of the notion that we should aspire to act and dress as much like the upper classes as we could manage and afford; a rejection of the notion that we should look—by donning dresses or suits, however well worn—as much as possible like ladies and gentlemen; a rejection of the notion that we should dress up.

Part of our attempt to turn notions of fashion on their heads was political: if not openly Marxist, then at least in the spirit of Roosevelt’s New Deal, which had been so inspiring to so many of our parents.

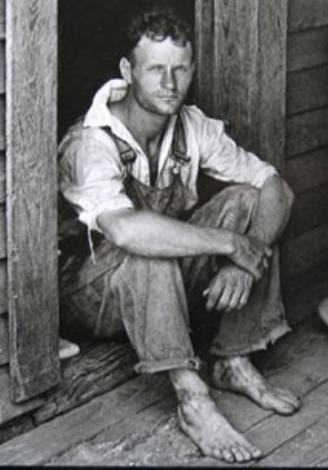

The heroes of a 1936 book that captured that New Deal spirit, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men—featuring wildly exuberant prose by James Agee and calmly respectful photographs by Walker Evans—are deeply impoverished southern sharecroppers during the depression:

The soft-spoken sharecroppers in Agee and Evans’ book wore blue-denim overalls, about which Agee rapsidises in detail and at length: “The bright seams lose their whiteness and are lines and ridges. The whole fabric is shrunken to size, which was bought large. The whole shape, texture, color, finally substance, all are changed…." (Yeah, I had a pair of dungarees like that.)

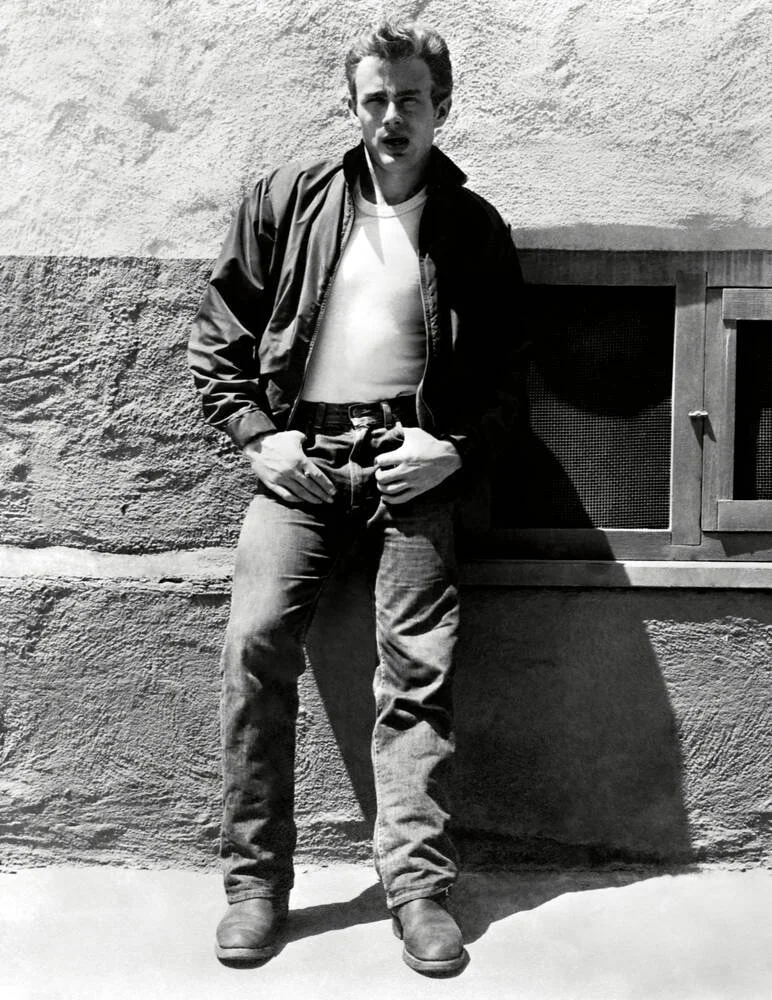

Some of this resistance to dressing up was youthful rebellion, as embodied by the character played by James Dean in Nicholas Ray’s 1955 film, Rebel Without a Cause.

James Dean, who died in a car crash a month before Ray’s film was released, wore blue denim pants in that film.

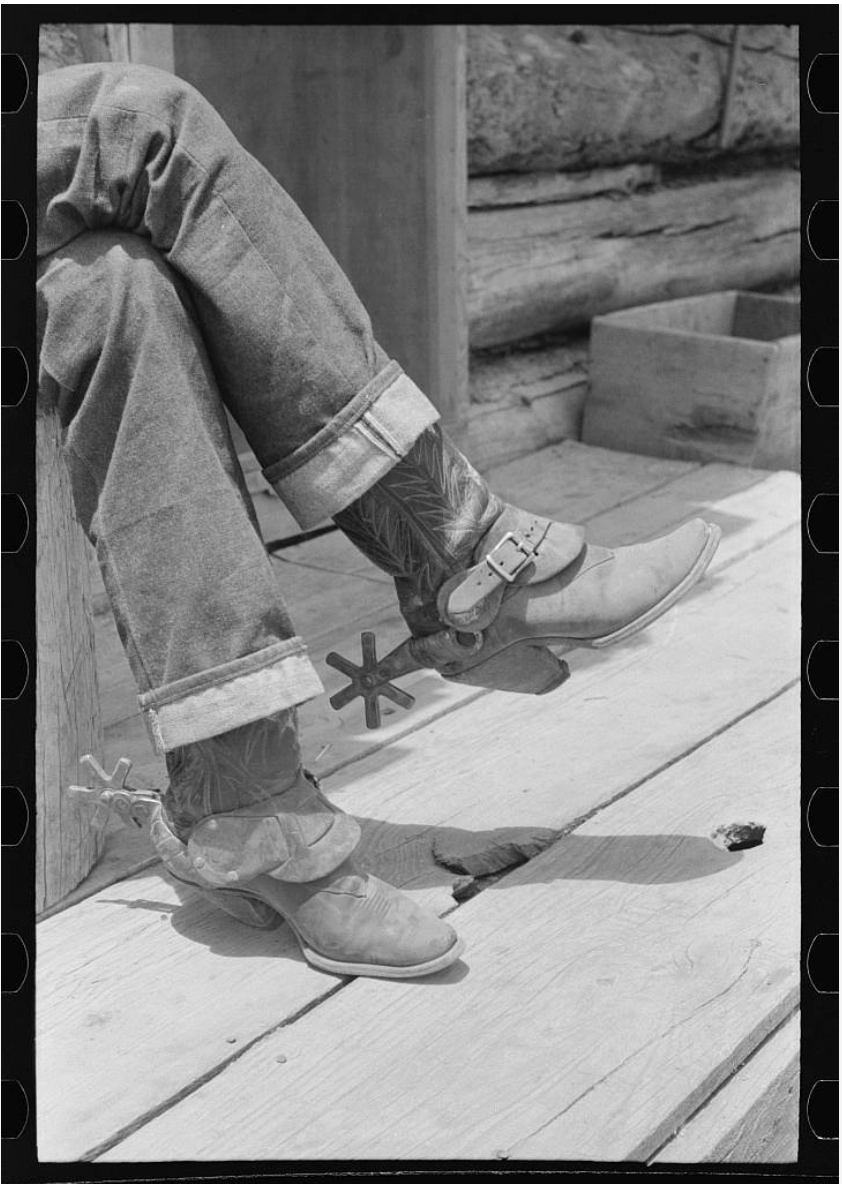

And, of course, most of the cowboys, who dominated TV at the time, wore denim:

The word “denim” comes from de (of) Nimes, that city in France; “jeans” comes from the French name for Genoa in Italy, Gênes; and “dungaree” comes from “Dungri" a village in India. All three towns were known for thick, heavy-duty fabric used to make clothes for working men.

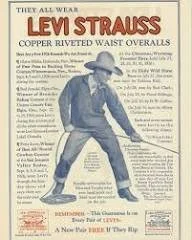

In the 1870s a Jewish immigrant tailor in Reno, Nevada, Jacob Davis, noticed how often a customer’s pants tore under stress at certain points. He suggested to Levi Strauss, from whom he purchased denim cloth, that they partner in producing work pants with copper rivets at those stress points.

Those would be the pants that changed the world.

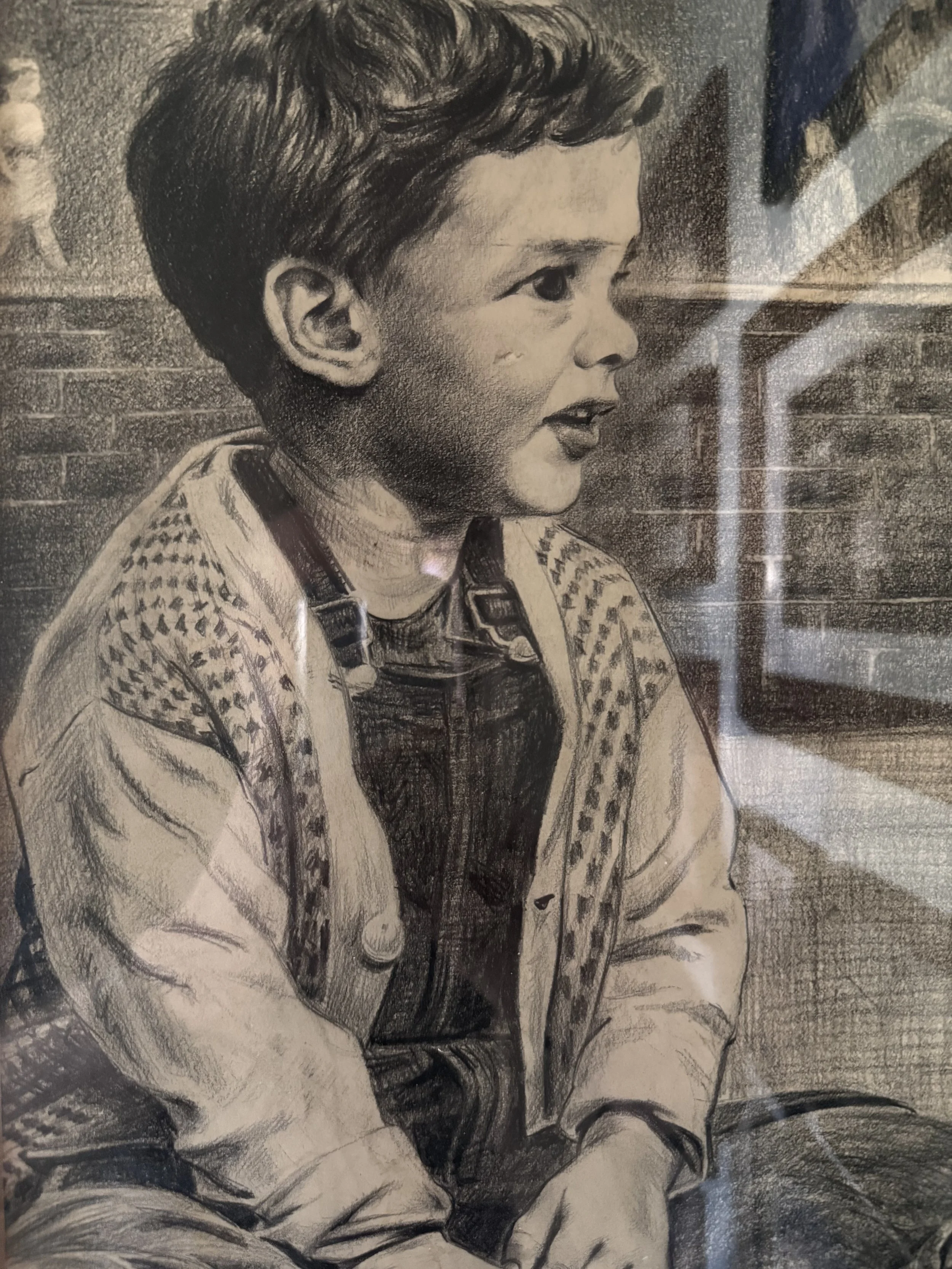

This was me, rockin’ a pair of dungarees in about 1953.

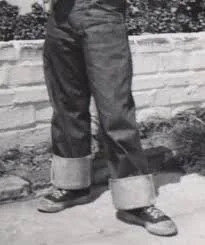

I wore dungarees—with cuffs rolled up so the lighter-colored inside showed.

But this was not me.

But dungarees, as we called them back in the 1960s, or jeans as I came to call them, looked better without cutting off the leg at the ankle.

I remember my shock when a new roommate at college turned out to have more than one pair of dungarees.

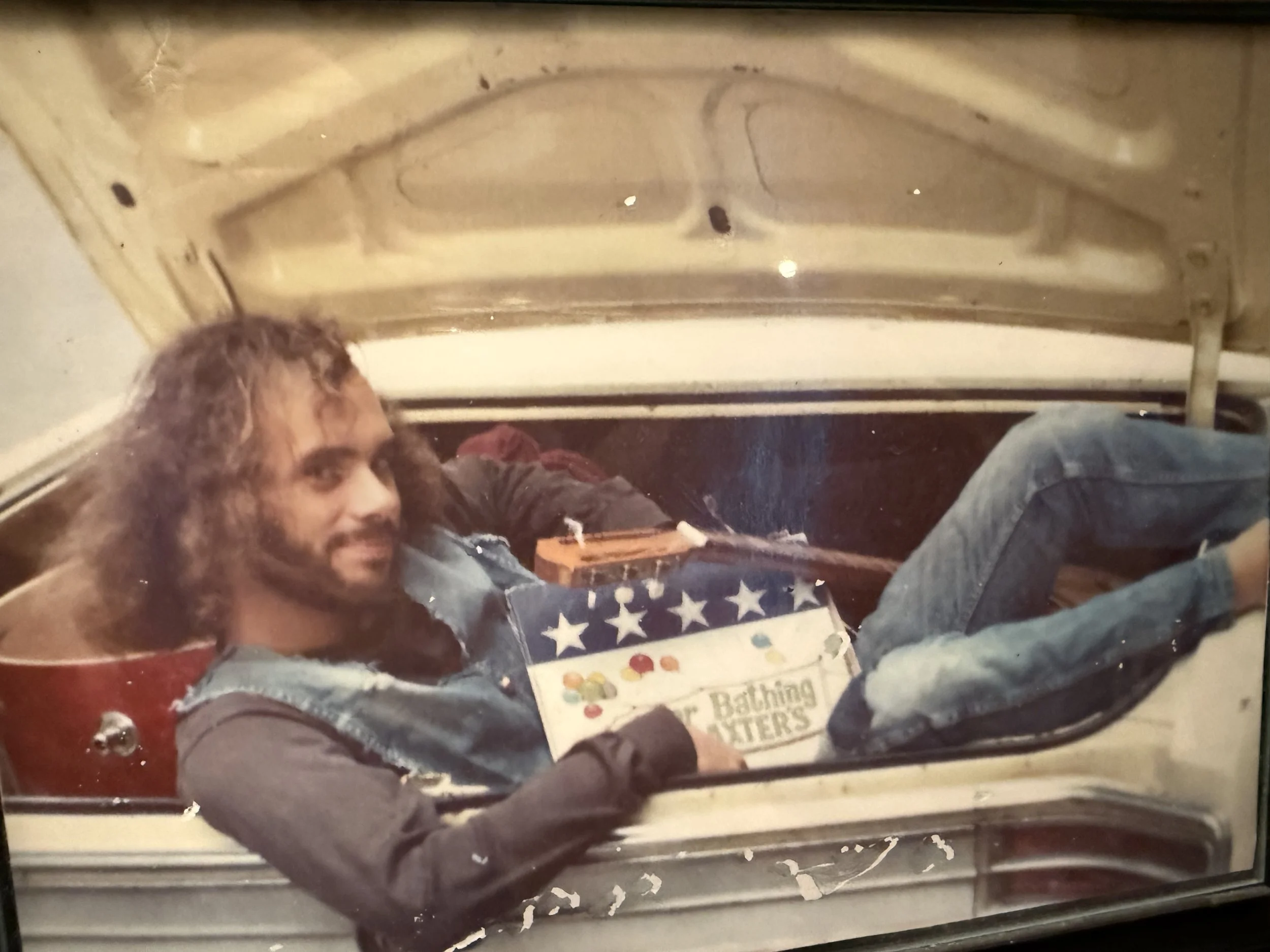

I, and most of us, kept wearing jeans when we grew up, when not at work. Then I, and many of us, also began wearing jeans when at work.

And I, and many of us, now wear jeans in retirement.

Jeans had become the American costume. And much of the world adopted that costume too.