The Books That Most Influenced Us

Although we spend much of our time these days glued to a screen, books still do play a role in our lives. If nothing else, they provide great living room décor.

And while their importance may have been diminished by our current slavish devotion to the digital world, books — particularly for the baby boom generation — have changed how we think, talk, write, vote, teach, learn and — maybe most important — how we see ourselves. Even if we haven’t read them, they have had a major impact on our lives.

Which ones, though, have had the biggest impact, been the most influential?

I’m not talking about favorite books, the ones we fondly remember where we can easily recall favorite passages or maybe have read again and again. I’m talking about the ones that have had the broadest, deepest, longest-lasting cultural effect.

There isn’t, of course, a specific measuring stick to judge that, which means everybody probably has their own metric and thus their own list. So, here’s mine, a personal list of what I believe are the 10 most influential American books of the last 75 years or so. (It easily could have been 15.)

I’ve arbitrarily decided to restrict the list to just American books, because those are generally the ones I know best, so no “1984” by the Brit George Orwell or “Wretched of the Earth” by the Frenchman Frantz Fanon or “The Handmaid’s Tale” by the Canadian Margaret Atwood.

Perhaps not surprisingly, a majority of the books on my list were published in the 1960s, a decade of extraordinary cultural ferment. And perhaps it’s equally unsurprising that there are no books on the list from the last couple of decades. Maybe that’s because the culture has moved away from books — and toward bite-size digital snippets — or maybe because my generation has moved away from the culture.

Finally, let me be the first to acknowledge: my choices are not necessarily the best books, nor the best sellers, nor even possibly the most interesting. They are, rather, the books I believe have had — and continue to have — the most impact on who we are today.

Here they are, chronologically:

The Catcher in the Rye, by J.D. Salinger, 1951

It was a touchstone for ’60s youth culture and the post-war generation, even if it came out before we hit our teen years. “Catcher” essentially created for us the idea of adolescent alienation and rebellion and maybe even the idea of adolescence itself.

I read it first when I was about 12, when I wasn’t supposed to, and yet for the first time, I had found a book that I felt really understood me. I then read it again, when I was 14, in the depths of early teen-hood, and then again at 17 or so. It’s meaning changed, and deepened, each time.

Invisible Man, by Ralph Ellison, 1952

There had been books about being black in America before, but they were generally overtly “protest” works, sociological or political statements. “Invisible Man” redefined what a “Black novel” could be.

It was surreal, comic, angry and lyrical all at once. And by being that it made the case for black inner life as complex, contradictory and universal as anyone’s. It was not, of course, a case that should have had to be made. It also made the idea of blacks being invisible a lasting metaphor, not because of literal absence but because of other people’s blindness.

Published just before the modern civil rights movement exploded, “Invisible Man” captured the psychological cost of racism just as the nation began to fully reckon with it and the book contributed to that reckoning.

Howl, by Allen Ginsburg, 1956

“Howl” didn’t just influence poetry, it blew open what American literature was allowed to sound like and talk about.

It shattered formal constraints with long, unwieldy lines. More important, it addressed subjects like queer identity, drugs, madness, sex, spirituality and rage. It helped launch the Beat movement, which rippled outward into music, politics, counterculture and later confessional and spoken-word traditions. You can probably draw a straight line from “Howl” to modern hip-hop.

Plus, the trial of “Howl” and its publisher on obscenity charges permanently widened the First Amendment space for artists.

On the Road, by Jack Kerouac, 1957

I have to confess: I don’t remember ever finishing this defining novel of the Beat Generation. It felt somehow impenetrable, or maybe I was too young when I first tried to read it.

It was difficult reading for me — messy, impulsive, unpolished. All of which made it an inspiration for the 1960s counterculture and our desire for the non-conformity and spiritual questing it championed.

To Kill a Mockingbird, by Harper Lee, 1960

Perhaps the single most influential novel taught in U.S. schools. It shaped how generations think about justice, race and moral courage.

On the other hand, that impact may have been more the result of the much-lauded movie adapted from the novel, with the heroic Gregory Peck and the villainous Bob Ewell character. But, of course, the success of the movie also steered people back to the book.

Catch-22, by Joseph Heller, 1961

How many books have pushed a phrase into common, long-term usage?

Although it focused on World War II, its satire captured the absurdity of the growing Vietnam War and also of bureaucracy at large. It was a comic breath of nonconformity reacting against the stultifying sameness of the Eisenhower years. It gave us permission to laugh at what we had become.

The Making of the President 1960, by Theodore H. White, 1961

Before White’s book, campaign coverage — in fact, most political coverage — had been little more than glorified stenography, the unmediated words of speeches, party platforms and so on. By focusing on the people involved, White’s book reinvented political journalism.

He showed how power is acquired and how it is used. Candidates started reading the book, and adjusting their behavior accordingly. They became more media-conscious. In a way, the book didn’t just describe politics; it changed how politics is practiced. It taught Americans how to watch elections — and taught politicians how they were being watched.

Silent Spring, by Rachel Carson, 1962

The book that launched the modern environmental movement. Perhaps more than any recent work, it led directly to policy change (bans on DDT and the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency, among others). Additionally, it altered how Americans understand science, nature and corporate responsibility.

I read it again recently, and while the writing can be beautifully descriptive at times, some of the technical parts are a bit slow-going. And some conclusions seem awfully obvious now. But it still holds up remarkably well.

The Feminine Mystique, by Betty Friedan, 1963

It didn’t start the feminist movement, but it greatly broadened it and ignited second-wave feminism. It named a problem millions felt but couldn’t articulate, what Friedan called “the problem that has no name.”

It changed family norms, workplace expectations and the political vocabulary around gender in America. And it led to organizing, activism and even a number of lasting institutions.

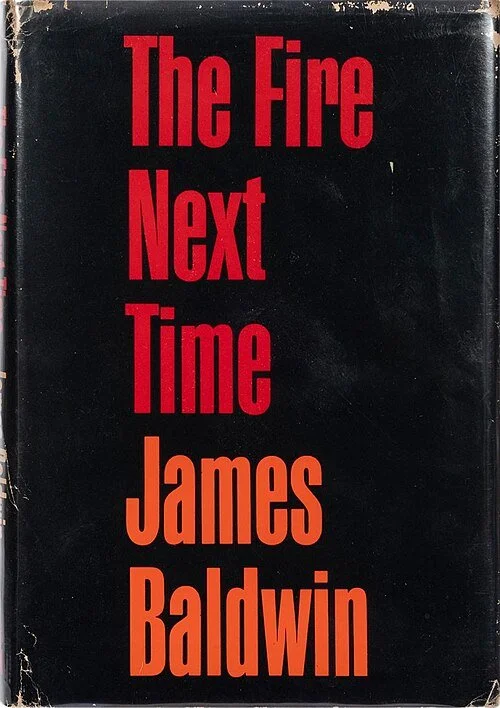

The Fire Next Time, by James Baldwin, 1963

Baldwin was the moral conscience of the civil rights movement. He didn’t beg for sympathy or reassurance. He told white readers that racism was their spiritual and psychological problem, not simply a black grievance.

Baldwin foresaw an America erupting in racial violence unless that problem was addressed. Arriving right before the March on Washington, the book became a kind of moral handbook for a country teetering on the edge and sometimes falling off it.

Honorable Mentions:

The Autobiography of Malcolm X, by Malcolm X and Alex Haley, 1965

The Electric Kool Aid Acid Test, by Tom Wolfe, 1968

Portnoy’s Complaint, by Philip Roth, 1969

Ragtime, by E.L. Doctorow, 1975

Beloved, by Toni Morrison, 1987