the rise of “wrap rage”

In the fall of 1982 Edmund R. Donoghue, chief medical examiner for Cook County, Ill., asked one of his investigators to smell an open bottle of Tylenol capsules at a possible crime scene.

When the investigator, Nick Pishos, detected the aroma of bitter almonds, he and his boss were all but certain that the bottle contained potassium cyanide, and that the cyanide was most likely contained in the bottle’s Tylenol capsules. They also concluded—and lab analysis later confirmed—that the capsules had just killed three people in the same family.

What they could not know was that their discovery would change forever the way nearly all products—not just medicines--would be packaged and sold all over the world.

They could not foresee the phenomenon of “wrap rage.”

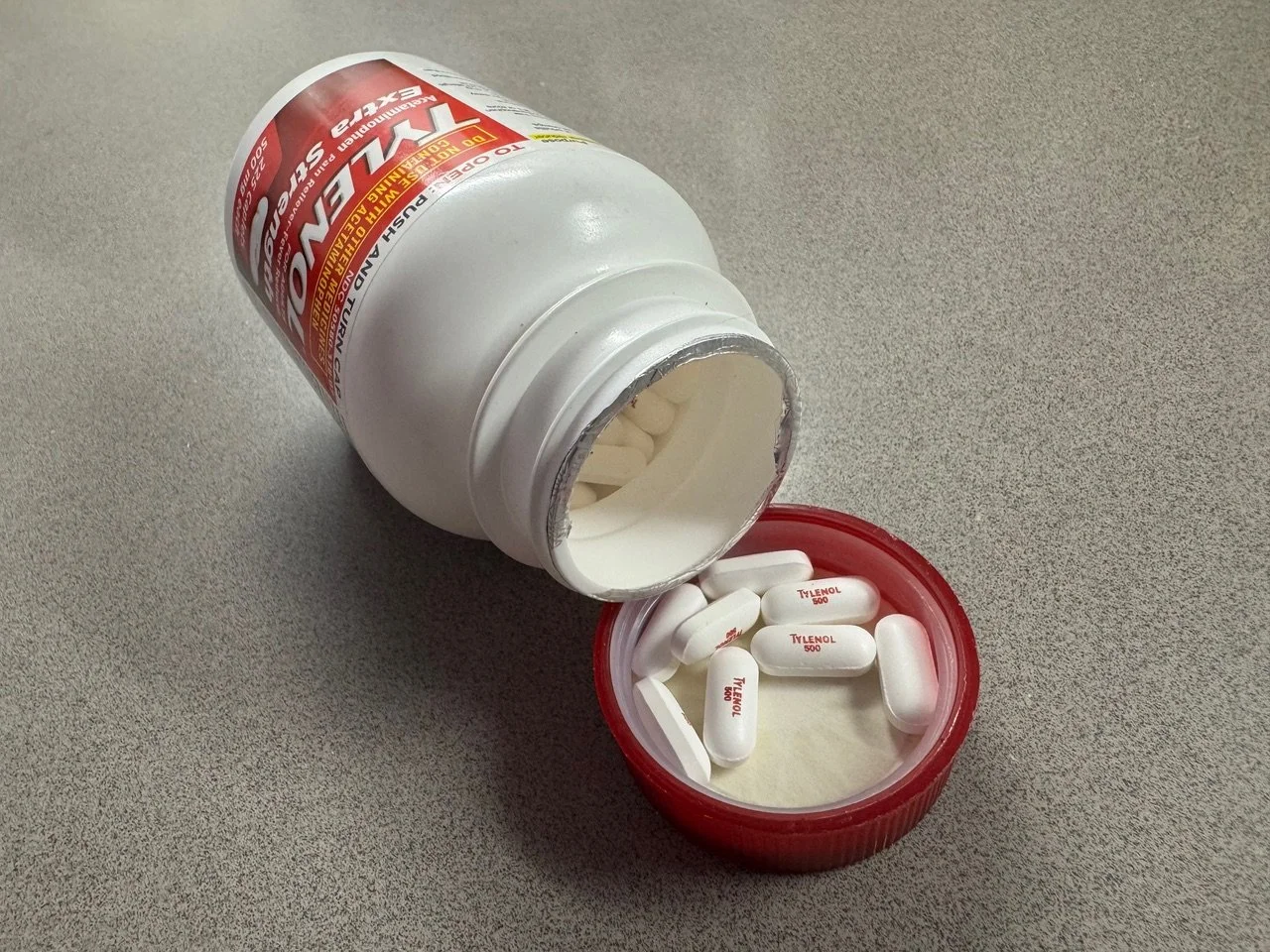

Today you can’t go anywhere to buy anything—yes, I mean anywhere and anything—without feeling the consequences of the “Tylenol Murders.” At least seven deaths were attributed to tainted gelatin capsules of Extra Strength Tylenol that were filled with lethal doses of cyanide. Police theorized that someone shoplifted packages of the popular pain pill, pulled open the gelatin housing on some of the pills, then put the deadly packages back on store shelves, waiting for random people to buy the pills, take them and die.

Amazingly, no one to date has been charged with the murders, although copycat killings, involving other drugs like Excedrin and Anacin, also were investigated at that time, resulting in at least one conviction.

Today, Tylenol’s response to the use of its popular analgesic as a murder weapon is taught in business schools. As its market share plunged from 38 percent to 8 percent, Tylenol’s manufacturer, Johnson & Johnon, coupled a massive and swift recall with the then-novel introduction of tamper resistant/tamper evident packaging. Ultimately, it redesigned the pills themselves, introducing solid “caplets” to replace powder-filled capsules.

Within several years, Tylenol regained its No. 1 market share.

Anyone of sound mind would applaud this outcome. But I think a case can be made that what also happened after the Tylenol Murders was a huge case of—shall we say—overkill, prompted not by public safety, but by inventory control and the bottom line.

It’s the old “Induction Seal”/”Clamshell Packaging” conundrum.

Induction seals are the reason you can’t just unscrew a jar of ketchup or orange juice and pour it out. These annoying, and near impossible to remove barriers sit atop every container of over-the-counter pills, and almost every bottle of human-ingestible liquid or semi-liquid that you buy at the grocery. (And those that don’t have induction seals are riveted closed by tamper-evident screw tops that grow more impossible to twist open as each year passes through your arthritic hands.)

Still, this keeps some wacko from doctoring our Dr. Pepper or Minute Maid.

It’s really clear plastic clamshell packaging that gripes my aging, grumpy butt.

Hailed as a great way to show off all manner of products, injection- or heat-molded plastic packaging has been around for more than two decades. Not surprisingly, its introduction almost immediately gave rise to the term “wrap rage” or “package rage” because said packages were so !@*&%!! hard to open.

But that was the point. After all, if you had a reasonably valuable product to sell (or one that was so small it easily could be thrust into a miscreant’s pocket, wouldn’t you agree that …

Thieves are likelier to steal a product that they can easily hide in a pocket. A clamshell package is usually bigger than the actual product, so it is harder to conceal.

Clamshell cases are most often tightly sealed, requiring the package to be opened with a knife or scissors. This means thieves can’t easily open the package in the store and slip the smaller item into their pocket.

· Another major benefit to packaging a product in clamshell packaging is to protect it from damage. Because most clamshells are made to mold to the product’s shape, it is less likely to be damaged in shipping or if dropped in the store. This protects both the manufacturer and retailer from damaging items from their inventory.

But help, as they say, may be on the way.

Already, one can find some, though hardly all, clamshell packaging with pull-apart openings at the back. But my bet is that most manufacturers will not be willing to fund such a re-design, especially for hardware items.

Which would leave me as I was a couple of weeks after I bought a heavy-duty staple gun. I couldn’t quite figure out how to load the damn thing—and when I took a scissors to the clamshell, quickly discovered that I had cut the deftly hidden instruction pamphlet right in half.

Frank Van Riper is a Washington, DC-based documentary photographer, journalist, author and lecturer. During 20 years with the New York Daily News, he served as White House correspondent, national political correspondent and Washington Bureau news editor. He was a 1979 Nieman Fellow at Harvard.