Favorite Films by Decade: the 1970s

My assignment: Choose a movie from each decade of my life that has had the most personal impact, starting with the 1940s and ending in the 2020s.

We’ve already covered the 1940s, ‘50s and ‘60s, and continue today with the 1970s, which saw the rise of a “New Hollywood,” the emergence of a host of young directors and general recognition by critics and historians as one of the most creative decades in the history of American film.

These aren’t necessarily the “best” movies of the decade or the most innovative; they represent the films that resonated most with me, either from my initial viewing when they were released or when I first engaged with them in subsequent years.

Some rules to keep these lists doable: 1) Only one film each decade by a particular director; 2) only English-language movies, due mainly to gaps in my knowledge about foreign-language films except for Italian neo-realism, French New Wave and the works of Akira Kurosawa, and 3) no TV miniseries.

I’m sure I’ve missed some great movies that should be on these lists. Yet this still leaves hundreds, if not thousands, of movies to choose from.

Let the arguments continue.

The 1970s:

“The Godfather” (1972)

This is my favorite American movie. Writer/director Francis Ford Coppola took Mario Puzo’s enormously popular novel and, with Puzo’s help on the screenplay, made this cinematic masterpiece.

Coppola’s career-defining work tells both the epic story of an Italian-American family as generations moved from Sicily to the Lower East Side to Long Island to Lake Tahoe, Nevada, and a tale of raw, unbridled capitalism in the form of the Mafia. Or as one Mafia Don says in a meeting of crime bosses, “After all, we are not communists.”

The film helped introduce to the public the formidable talents of actors Al Pacino, Diane Keaton, John Cazale, Robert Duvall, Talia Shire and James Caan, showcased outstanding performances in smaller roles by Sterling Hayden and Richard Castellano, and re-established the enormous talent of Marlon Brando, who won the best actor Oscar for his portrayal of Don Vito Corleone.

Every technical aspect of the movie is extraordinary, from Gordon Willis’ cinematography to Dean Tavoularis’ production design to Nino Rota’s music. And the film brought to American pop culture some of the most memorable lines in movie history, including “I’m gonna make him an offer he can’t refuse,” “Leave the gun; take the cannoli,” and “It’s not personal, Sonny; it’s strictly business.”

The rules for this film history series prohibit the inclusion of more than one movie per decade by one director, which is why Coppola’s “The Godfather: Part II” is not listed. And that movie is my second favorite American film.

Close behind:

“Annie Hall” (1977): Modern urban angst in New York and Los Angeles was never as funny as in Woody Allen’s greatest romantic comedy, starring Allen and, in the title role, Diane Keaton.

“Chinatown” (1974): A film noir set in the bright sunshine of Los Angeles in the 1930s, this is a cinematic gut-punch brought to the screen by director Roman Polanski, writer Robert Towne and actors Jack Nicholson, Faye Dunaway and (an incredibly creepy) John Huston.

“The Day of the Jackal” (1973): Fred Zinnemann’s taut political thriller set in France during the early1960s is about a hit man (Edward Fox) hired by retired French soldiers to assassinate President Charles de Gaulle after the “loss” of Algeria as a French colony, and the police detective (Michael Lonsdale) tasked with stopping him.

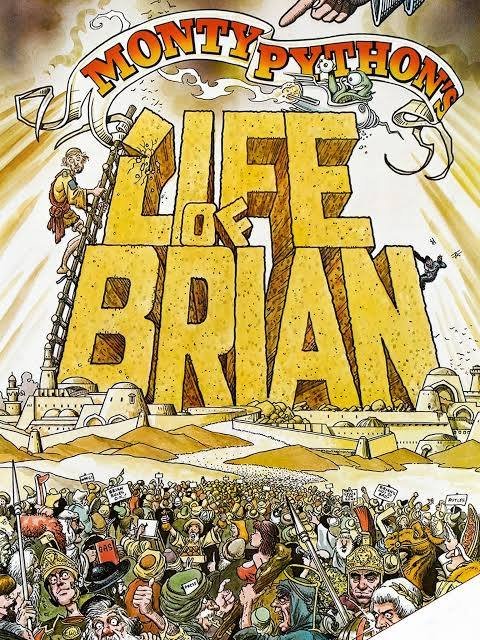

“Monty Python’s Life of Brian” (1979): Saved by the last-minute financial backing of the Beatles’ George Harrison, the members of Monty Python’s Flying Circus made this irreverent, sacrilegious and fall-on-the-floor funny story of Brian of Nazareth, who bears an uncanny resemblance to another favorite Son.

“Cabaret” (1972): Director Bob Fosse’s tale about a nightclub singer (Liza Minnelli) in Berlin during the Weimar Republic, with a great score by John Kander and Fred Ebb, adeptly juxtaposes the creativity and decadence of the era with the rise of fascism. Has there ever been a more chillingly prescient scene than the one of Nazi youth singing “Tomorrow Belongs To Me”?

But, perhaps you’re wondering, how could he leave out “Dog Day Afternoon,” “Mean Streets,” “All the President’s Men,” “Norma Rae” and “Young Frankenstein”?

Coming next week: The 1980s

Bruce Dancis spent 18 years as the Arts & Entertainment Editor of the Sacramento Bee, after previously serving as an editor for the Daily Californian, the San Francisco Bay Guardian, M.I. (Musicians’ Industry) Magazine, Mother Jones and the Oakland Tribune. He also wrote about Film and TV History in a weekly column about DVDs that was syndicated by the McClatchy and Scripps Howard news services. Since 2003 he has co-chaired a summer film program at the Three Arrows Cooperative Society in Putnam Valley, NY. He is the author of “Resister: A Story of Protest and Prison during the Vietnam War” (2014, Cornell University Press) and appears in the documentary film “The Boys Who Said No! Draft Resistance and the Vietnam War” (2020). He lives in Cardiff, CA, and Putnam Valley, NY.