Robert Plant, Bob Dylan, and Willie Nelson

Three Models for Active Aging

Robert Plant, 75, Bob Dylan, 83, and Willie Nelson, 91, performed a couple of weeks ago in Bethel, New York, as part of Willie’s “Outlaw Music Festival.” These three musicians have in common being accomplished, important, very old and still active.

So, let’s use them to consider strategies for active aging. For I think I can discern three distinct such strategies in their approaches.

Model for Active Aging # 1

“An Old Sweet Song”

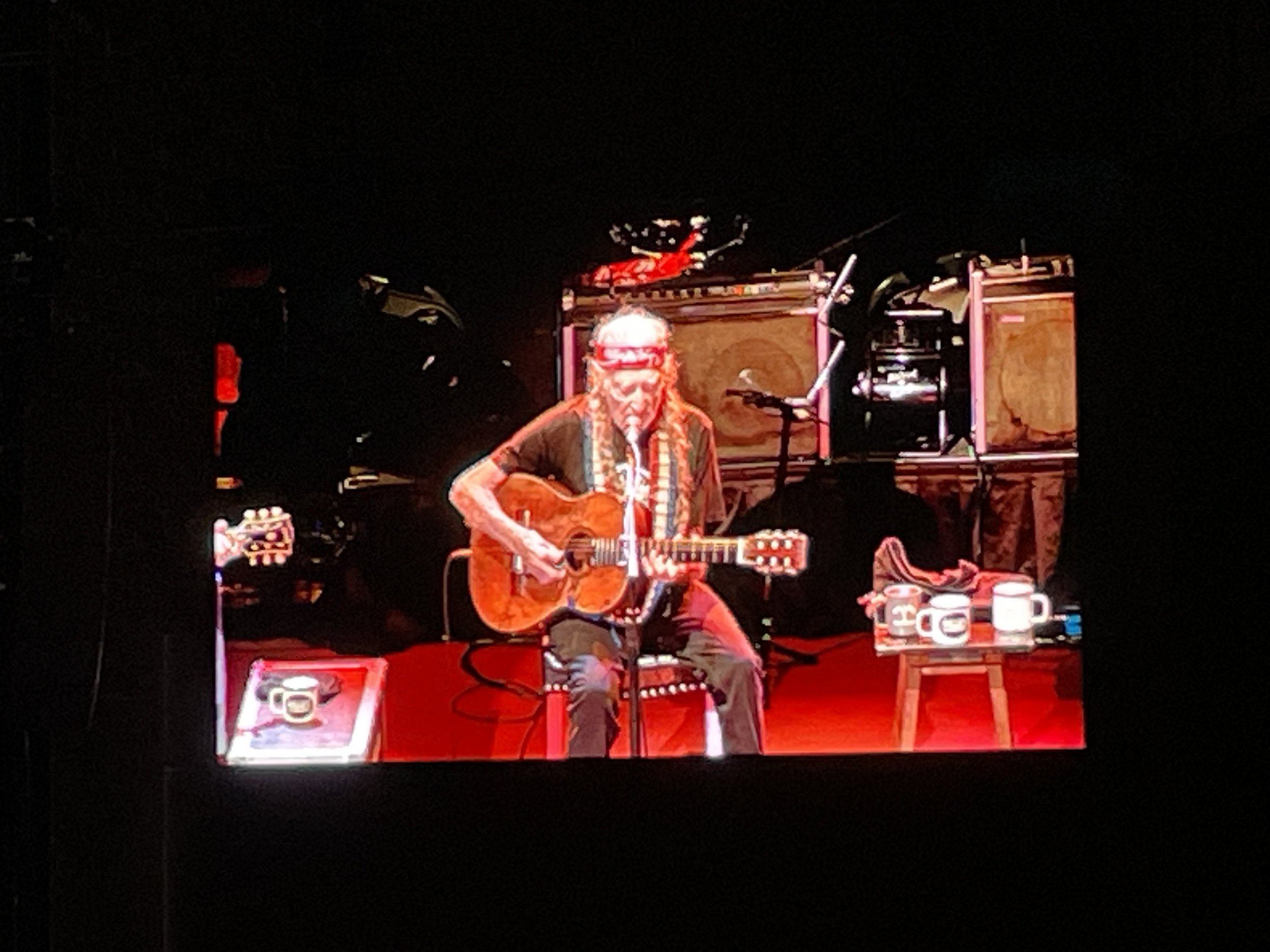

Willie Nelson took the stage last. He had recently missed a couple of shows due to illness. He now sits while he sings and picks, with his accomplished singer-guitarist son, Lucas, sitting to his left and the son of an old band mate sitting on his right.

And some beautiful music emanated from the ensemble behind them and from those three chairs, particularly the one in the middle. For Willie Nelson at 91 is still producing delightful guitar licks and still crooning in his characteristic understated yet emotionally resonant manner.

He put on a fine show.

Nelson’s classics were not slighted: “On the Road Again” (among the handful he played that he wrote), “Georgia on my Mind,” “Mama Don’t Let Your Babies Grow Up to Be Cowboys,” “Always on My Mind,” et cetera.

Long career. Lots of songs that he had made, as they say, his own.

Willie certainly wasn’t breaking any new ground that evening. More than half the songs he sang he had been singing back in 1980, when “On the Road Again” was the top country song in the country, and his “outlaw,” long-haired, marijuana-smoking persona might still have seemed quite rebellious. He sure enough had broken some new ground back then.

Willie Nelson at 91 did surprise me, at least, by singing a song by Eddie Vedder of Pearl Jam, “Just Breathe.” But even that, it turns out, he had been performing off and on for a dozen years. Not that the familiarity of his repertoire seemed to bother anyone in this adoring and enthusiastic crowd.

Willie Nelson old—very old—is a somewhat rickety and slightly tamer version of Willie Nelson young. He is, and seems content to be, a long, long way from anything anyone would call the cutting edge. This old man is still enchanted by a bunch of “old sweet songs.” And this old man is still enchanting.

Wouldn’t most of us be content to be a rickety, somewhat tamer version of our younger self as we enter our 90s?

Model for Active Aging # 2: “A-Changing”

Well, there’s plenty of evidence that Bob Dylan at 83 is not content with such a same-old-song old age.

In a sense Dylan is doing, at this advanced age, what he was always doing. But what he was always doing was not doing what people expected him to do. This is, after all, the musician who was booed for playing rock ‘n’ roll to folk audiences; then disappointed some rock audiences by playing country music; then annoyed his largely secular audiences by playing Christian tunes.

Nowadays he regularly disappoints by not playing what might qualify (the competition is stiff) as his greatest hits. I go to see him whenever he is in town, but at no time in this decade have I heard him play “Like a Rolling Stone” or “Blowin’ in the Wind” or “Mr. Tambourine Man” or “Just Like a Woman.”

Because Bob Dylan—né Robert Zimmerman—is always in the process of inventing a new Bob Dylan.

“Shedding off one more layer of skin,” is how he puts it in what might be my favorite of all his extraordinary songs, “Jokerman.” He also provides, in that song, an explanation for this compulsive transmigration: “staying one step ahead of the persecutor within.”

Among the skins Dylan has revealed lately have been a Frank Sinatra-like chanteur and, in his most recent album of original songs, Rough and Rowdy Ways, a Whitmanesque poet. He keeps the same basic band—four or five accomplished rock or roots musicians—but the type of music he is exploring and even his attitude toward his own enormous catalog regularly morph.

For this “Outlaw Music Festival” Dylan reincarnated himself as one of his earliest selves, one that predates even the Woody-Guthrie-esque folksinger. Now he’s an old-time rock ‘n’ roller. So, we got a Chuck Berry song, “Little Queenie”; a 1958 tearjerker by the Fleetwoods, “Mr. Blue”; a driving, early 1960s country-rock standard, “Six Days on the Road”; and, as a bonus, a Grateful Dead tune he’s been playing for a while, “Stella Blue.”

Which was all fine, fun, although, yes, also somewhat disappointing. For, as an interpreter of others’ songs, Bob Dylan is not Frank Sinatra or even Willie Nelson. And this fellow has no shortage of good original songs of his own that we might enjoy hearing him sing instead—arguably more good original songs of his own than anybody else ever.

In fairness, Bob Dylan and his tight band did perform 10 Bob Dylan songs that evening, including such gems as: “Shooting Star,” “Love Sick,” “I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight,” “Simple Twist of Fate” and, even, “Highway 61 Revisited.”

And maybe I’m overthinking this. Maybe Bob just grows bored with singing the same old songs, even when they are his great old songs. Maybe he just requires new material and new genres to remain interested, and isn’t perpetually evading some sort of “persecutor within,” who questions his current schtick.

Either way Bob Dylan’s version of old age involves repeatedly setting off after something new, something different, even if what seems new and different has been expropriated from the past.

And in case you’re wondering how many such new old roads a man can walk down? The answer clearly is a whole lot, since Dylan, though now a bit stiff legged, is still exploring different routes at age 83—still singing and playing (piano now, not guitar), still holding a harmonica up to his mouth, still surprising, still challenging and, sometimes, still disappointing his audiences.

Indeed, some in the audience—there to see Willie—were audibly talking through his set the other night.

Want to live a Bob Dylan old age? Don’t try to “please her, please him,” instead keep in mind that the world’s “still in spin” and remain “a-changin’.”

Model for Active Aging # 3:

“Still Time to Change the Road You're On”

All Robert Plant did in the 1970s was co-front what was arguably the world’s top rock band: Led Zeppelin.

A generation of young men found energy and strength in Jimmy Page’s intensified blues riffs (staples of the repertoire of many a dedicated air-guitarist) and Robert Plant’s soaring, strutting, blues-derived lyrics. Along the way, Page and Plant were helping invent a genre: heavy metal.

And the presence of some acoustic-guitar interludes, and eastern or English-folk-song-influenced passages made all that strutting seem a bit less bellicose, even artsy.

Led Zeppelin crashed and burned just after the 1970s ended, when their extraordinary drummer, John Bonham, died, following a day of prodigious alcohol consumption. There was the occasional performance after that, but the band never managed another tour, mostly because Robert Plant resisted such a journey back in time.

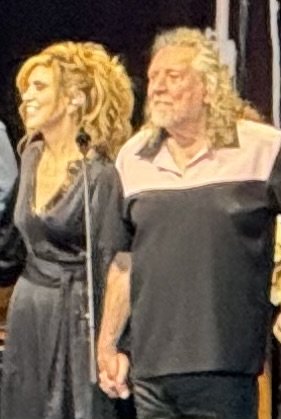

Now here was Robert Plant—having indeed journeyed forward not backward—singing, in tight harmonies, with a bluegrass singer born the year “Stairway to Heaven” was released, a rather accomplished bluegrass singer.

Alison Krauss, a musical prodigy, first entered a recording studio when she was 14.

Robert Plant had never won a Grammy until Led Zeppelin received a Lifetime Achievement Award in 2005. Alison Krauss won her first Grammy in in 1990, when she was 19. Only three musicians have won more Grammys than she: 27 and counting. And five of her Grammys, including Album of the Year and Record of the Year, were shared with Robert Plant for their initial collaboration, released in 2007: Raising Sand.

It was assembled under the guidance of legendary producer T-Bone Burnett.

It sold almost a million copies.

It is a beautiful album, indeed. Krauss’ soprano and Plant’s tenor create a tight but redolent harmony that is greater than either of its parts.

And they give magnificent concert.

Robert Plant today is a grizzled, lanky, leonine presence, with gray-blond hair cascading down the back of his head.

He, Krauss and a remarkably talented band, which includes her brother Viktor Krauss, squeezed in three songs Led Zeppelin recorded: “The Battle of Evermore,” “When the Levee Breaks” (originally recorded by Memphis Minnie in 1929) and my favorite Zep song: “Rock and Roll.”

Plant’s falsetto ain’t what it used to be, but when he strained, in “Rock and Roll,” for some version of the old ethereal “oh yeah, oh yeah” and the song’s denouement, “long lonely, lonely time,” he and I and much of the audience broke out in smiles.

Dare I say that my 74-year-old self found this 75-year-old’s music richer, deeper, more emotional, if less world-conquering, than my 20-year-old self had found the music of Plant’s 1970s band?

When introducing the members of the band, Plant thanked Krauss, for giving him “a second career.”

They sang that evening some things that were old, some things that were blue and lots that were borrowed. What was new?

Many of the genres this 75-year-old man has immersed himself in were new, as were many of the songs he was singing and many of the harmonies he helped bring forth.

But I was most impressed by the fact that Robert Plant had created for himself a new career.

That is not an easy old age to achieve. It may be the one it is most worth aspiring to.